**This article will appear in full in the next issue of The DESK**

Government bonds are described as a ‘risk-free’ instrument, on the basis that governments can always raise taxes, legally enforcing an inflow of cash. However, dealers can go bust holding these bonds.

Two, mirror-opposite bankruptcies demonstrate how assumptions about interest rate movements – and their speed – can catch out sell-side institutions.

Silicon Valley Bank held long-dated US treasuries in its hold-to-maturity portfolio as risk-free assets, but their value fell as new bonds had been issued at higher rates. If they had been held to maturity, this would not have impacted the bank, however when they had to be exchanged for cash, their fall in value was realised as a loss, and the firm defaulted on 10 March 2023.

While SVB is the second largest US bank default in 20 years, it is also the second sell-side firm to go broke by holding government bonds in that period.

MF Global went bust in October 2011 after betting approximately US$6 billion the wrong way on the value of European government bonds. In this case, the business had been suffering due to the low interest rate environment which had hurt its margins, and bought into govies as they offered better returns with European government bonds appearing to be cheap. The assumption was that European economies would improve, reducing rates and driving up the value of these bonds.

The firm expanded its exposure, and this became public knowledge, ultimately when a shortfall in segregated client accounts had to be reported to the regulator. Client funds and loans had been used to support the strategy, with repurchase-to-maturity agreements being used which reduced the apparent risk on the balance sheet. As the bets being made by the firm were not generating profits, its positions collapsed as customers demanded their funds, creditors asked for collateral and the share price collapsed.

The extent of missing client funds became apparent once a buyer for the firm examined its books and it shut down at the end of October 2011.

Beyond demonstrating different risks from holding bonds, these tales also carry tales of caution for buy-side traders.

The first impact is on the banking sector. In the case of MF Global, buy-side clients found funds were inaccessible. While firms like SVB typically do not have capital markets businesses, any sell-side firm running a similar strategy or asset mix will need to prove they are not a risk to counterparties or the wider market.

On 14 March 2023, Susannah Streeter, head of money and markets, at Hargreaves Lansdown described the response as, “US banking stocks are on a rollercoaster ride, rising sharply following the steep sell-offs yesterday as worries seem to be lifting a little about contagion from the SVB collapse. Hope is rebounding that the backstop of deposits of failed banks will stem further withdrawals and that more generous loan terms to struggling banks could help restore confidence.”

Yet on 15 March 2023 concerns set in again, triggering a wider sell-off in financials.

Mark Haefele chief investment officer, UBS Global Wealth Management wrote, “It’s important to note that from a solvency perspective, potential mark-to-market losses are far smaller than the US bank capital base. Even if we assume that the US$620 billion of unrealised losses that the FDIC estimates are held in the banking system were in fact realised, the impact on the capital ratios of the US banking system would be manageable. Silicon Valley Bank was virtually the only US bank that had close to negative equity if mark-to-market losses on securities were included. Furthermore, the Fed’s liquidity facility largely eliminates the need to recognize the losses on the securities portfolio, and the decline in bond yields over the last several days will reduce the size of the unrealised losses.”

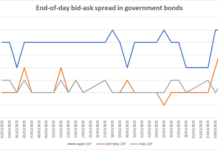

The second notable effect is on markets, and therefore traders. Despite reports of apparent banking sector stability, markets nevertheless seesawed in response to the SVB default as investors become risk-off, and short-sellers became active in the markets.

The post-SVB situation led the US 2-year Treasury to post its largest three-day decline since aftermath of 1987 stock crash, according to CME data.

Buy-side firms can also get caught by the mismatch between bond value and a need for cash, notably if they hold leveraged positions. The situation SVB faced with govies had echoes of the UK’s liability driven investment pension fund crisis in September 2022.

In that instance, the funds had to sell their government bonds to raise cash to support margin calls on leveraged positions. These funds were forced to sell into a market that saw UK government bond values falling steeply as the market expected rate to rise steeply in order to get buyers for newly issued debt. That crisis also reflected the steep fall in market value of bonds triggered by rapidly rising rates.

Post-SVB, leveraged positions, typically taken by hedge funds, needed to be unwound however the depth of book in S&P 500 e-mini futures fell to US$2 million on 14 March, the lowest level since the March 2020 sell-off and an 88% fall since the start of the month; similarly depth of book for on 10-year bond futures hit US$19,000 from an average of US$144k and also the lowest level since March 2020.

While long-only funds were less affected by these issues, hedge funds faced the potential inability to unwind leveraged trades.

For long-only buy-side firms, shorter term downward pressure on securities created buying opportunities if they had confidence, allowing those with the right trading tools and data to seize the moment.

A third, longer-term impact will be led by the 20 March interest rate decision. Expectations were that rate would rise but the seeds of doubt have been sown, Barclays and Goldman Sachs changed their expectations to a ‘hold’ – with Barclays emphasising this could just be a pause in future rate rises.

The Fed’s decision could directly impact the attractiveness of equities, and secondary market value of bonds, while also influencing new bond issuance. With big moves resulting from that decision, impact on the central bank would be the biggest effect of a bond-based bank default.

©Markets Media Europe 2023

©Markets Media Europe 2025