Understanding the difference between commercial and public data offerings is crucial for data users. A good example of this difference can be found with a reclibration of reporting requirements to the US post-trade tape for bond prices, the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE).

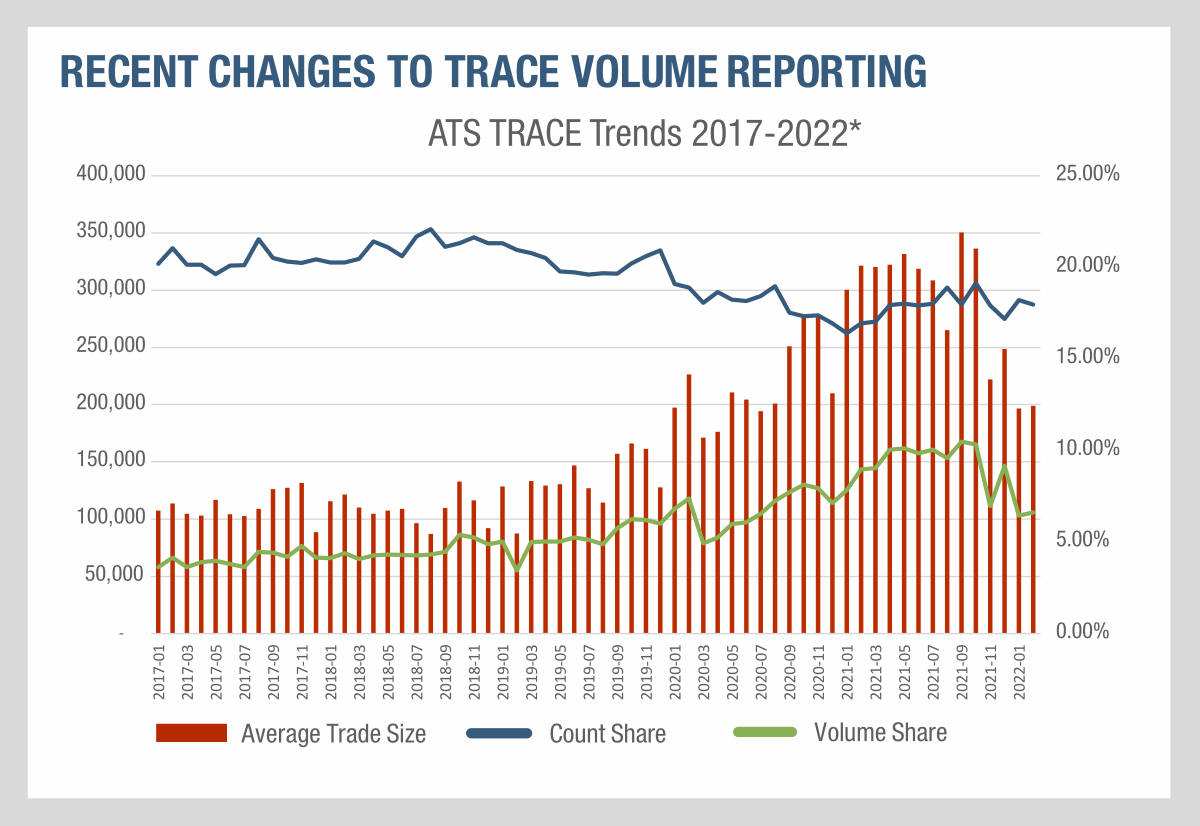

On 12 July 2021, FINRA, which operates TRACE, issued a notice which changed the way that reports posted by alternative trading systems (ATSs) would be published so that “only one report for an ATS trade is included.”

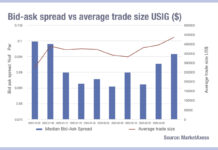

This sensible approach to improving the validity of data being consumed curiously led to a drastic change in what was reported. It had appeared that between 2017 and the summer of 2021, the size of trades on ATSs had increased considerably. While the count had meandered about, trading volume grew, according to MarketAxess data, from an average of US$107,000 to US$319,000, meaning that the size of each trade became considerably larger.

What happened when the new rules came into play was also notable. Clearly trades reported via ATS platforms were inflating volume on the TRACE feed. This appears to have been due to double counting of trades. Following the change in 2021, count share did not change but the average trade size by volume was cut in half, from a peak of US$350,000 in June to US$150,000 in December.

The debate around the value of a consolidated tape is a live one in both the US and in Europe. Getting the wrong steer on trading activity from any given data source can seriously affect pre-trade decision making and the quality of trade execution an investment manager or dealer can achieve. In both jurisdictions there have been heated discussions around the speed of disclosure and caps on trade size disclosure.

In Europe, prevarication has meant just getting a post-trade tape of prices has been a challenge, some 18 years after the US set one up.

There are clear lessons for both jurisdictions from this case. While commercial data providers get clear feedback – and have an economic incentive – to ensure trading data provides a valuable reference point, tapes managed by regulatory authorities exist to fulfil the goals of the regulator. Under MiFID II the promised transparency failed to materialise but it took years for European authorities to pull the plug on some relatively useless reporting requirements. If a trader need that data source to power decision-making analytics, these might be compromised if the feedback loop on data quality is not effectively improving it.

In this case a correction was made, but only after an 18 month period of apparent misrepresentation. Understanding not only the quality of data, but also the potential for anomalies to occur in the provision of data and the need for a feedback loop to correct that, are all key to the use of data.

©Markets Media Europe 2025