The DESK examines the different sizes, protocols and feedback traders can use on each side of the Atlantic to execute corporate bond orders.

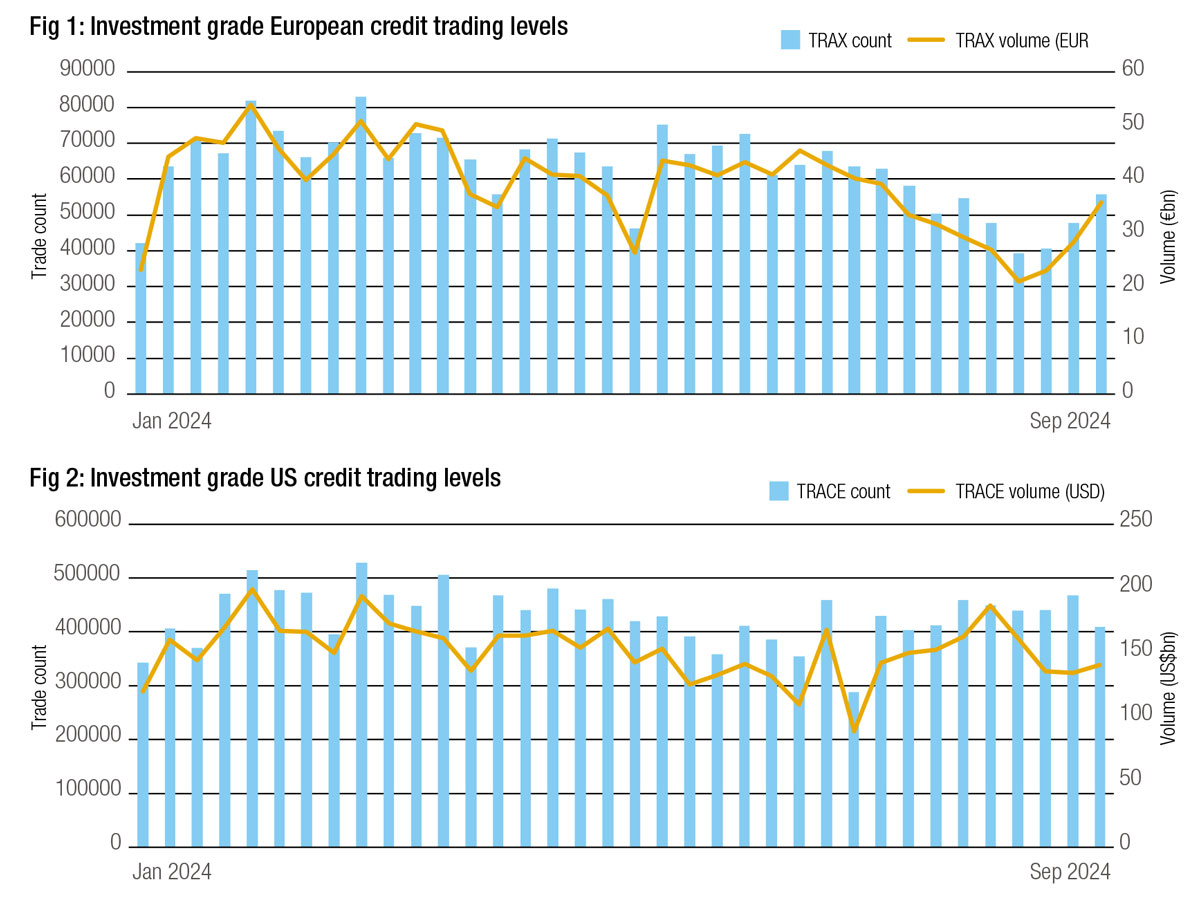

While US and European corporate bond markets have both electronified over the past ten years, they have also diverged in significant ways. Traders get increasingly different access to liquidity and pricing, while each has a unique regulatory framework.

Chris Coccoluto, global head of trading at Manulife IM, says, “US liquidity is strong with increasing trading volumes, the emergence of portfolio trading and algo pricing really helping to facilitate a far more efficient market. High grade liquidity is in a really good spot.”

Peter Welsby head of European FICC trading at Manulife IM, says that European market liquidity is relatively thinner. “It’s not bad, but it’s not as strong as the US,” he says. “European markets are often more technical. You’ll end up with certain tenors seeing buyers from fixed maturity funds, others that are seeing demand from global funds and certain tenors where new issues are dominating. That applies to names as well as parts of the curve, so it becomes a lot more technical.”

Jason Recordon, head of credit trading Europe at Janus Henderson says, “The US is a single country, and US markets are also five times bigger than Europe while the UK is about a 10th of the size. A standard Sterling [new issue] deal is US$300 to US$500 million, while a benchmark Euro deal can be anywhere between US$500 and US$1 billion, while in the US trades they can be much larger.”

Each market has a certain inherent capacity to manage liquidity due to the level of coverage and service it gets from the sell-side and market makers.

Andy Munro, global head of fixed income trading at Janus Henderson, says, “The UK and EU have bigger minimum denominations in corporate bonds compared to the US, this makes the market harder for retail investors to participate in, and also makes the fair allocation of partial trades harder to manage especially if some of the funds are relatively small compared to others on an order.”

“Balance sheet commitment and willingness to take down risk in European currencies differ to dollars, because the banks’ ability to shift that risk is completely different,” Recordon notes. “A sterling asset will probably sit on your balance sheet for a lot longer time than a euro or dollar asset, so sterling dealers are a little bit more reticent to take on risk, and there are fewer. In Europe, you might have 10 to 15 houses who can shift European risk, but probably only five to eight who can trade Sterling properly. While they’re likely to see a lot more of the flow, they can also therefore get clogged up a bit faster than in other markets.”

Dealer behaviour and relationships

The relationship between dealers and buy-side trading desks also differs between both markets. Anecdotally, the US is described as more relationship driven, with greater connection between primary and secondary market dealer relationships, while European markets ex-UK are less relationship driven.

Munro says, “We think there’s a tendency to put people in competition more in Europe than there is in the US. Part of that is the greater transparency in the US, and it’s a far deeper, broader market, due to the wider proliferation of exchange traded funds (ETFs) that have taken off, adds to greater transparency and confidence in where the markets are.”

That transparency can make trading with multiple dealers more problematic as the dealers are then more exposed as to positions they have taken on. Another factor may be Europe’s Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II), which sets out a requirement for ‘best execution’, sometimes interpreted as requiring several dealers to be put into competition (‘in comp’) on any trade.

“Maybe people in Europe take MiFID in a different way than we do, and the interpretation of demonstrating best execution perhaps differs,” says Welsby. “Perhaps there are other reasons they split a block up across multiple people on the street, or quote five or six banks in competition for a large piece. I would like to think that it’s to do with MiFID rather than anything else.”

Coccoluto notes that the need for strong buy and sell-side relationship is universal.

“We still place an immense importance on the partnership model,” he says. “We’ve reached an efficiency in smaller trades executed electronically but when it comes to larger trades, who you choose to trade with matters. You can’t show up at the doorstep looking for balance sheet when volatility spikes, if you’ve never partnered with folks.”

Protocol adoption

Market size, transparency and behaviour all have an effect in the success of different trading protocols in the credit market.

Neal Rayner, head of US trading at Janus Henderson says, “You can do larger portfolio trades (PTs) here, partly because it’s a lot easier for bulge bracket banks and some smaller players to hedge out their risk very quickly using ETFs, credit default index swap (CDX) and a number of other tools.”

Traders observe more of a tendency in the US to go use PTs than in Europe; while orders with many line items will be processed via PT in European markets orders of 50 to 100 lines or less will often be traded in other ways.

“To say we’ve had some success in PTs, especially large dollar PTs is probably the understatement of the year,” says Munro. “We’ve been very pleasantly surprised with the sizes that we’ve been able to execute at excellent levels. That said, we did our first EM PT in the last few weeks which is multi-region, multi-jurisdiction. The PT game is progressing at speed.”

He notes that loss-leading efforts to gain market share by dealers are no more and that the PT market has now normalised on both sides of the pond.

“Every so often, you have a new entrant into the market who will put out ultra-aggressive levels to win market share,” he says. “Even outside of those, sometimes the competitiveness between the banks is quite astonishing, it might be less than a penny difference on the overall pricing of a PT idea.”

Direct streaming of prices from banks to clients, potentially enabling low-to-no-touch trading, was very popular two years ago, but trading venue perimeter rules put in place by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) made many people wary of using execution management systems (EMSs) to handle direct dealer connections.

“I’ve heard from investment banks that direct connectivity and the ability to click to trade is farther ahead in the States but both buy and sell side need to be mindful of the costs, we may make savings from not paying execution fees to venues but we have to consider the impact of supporting these additional connections,” he notes.

Appetite is still there, traders observe, with positive outcomes for buy-side clients and dealers continuing to making outreaches of these services.

“We do have one US bank that we’re potentially lining up to do it on a direct feed into our OMS. Even if we can’t click-to-trade we would like to start seeing differentiated axes coming directly into us,” says Munro.

Platforms, transparency and control

Where direct connectivity costs are too high, there is evidence that the sell side is happy to engage directly using platform infrastructure more than before.

“We’ve noticed in response levels that dealers have become agnostic to which platform we use, and that’s great,” says Coccoluto. “In the US we’ve seen what was historically a single platform dominant market for credit trading, changed to multiple platforms that have real staying power in their market share and in their offerings. With that comes more competition, which I think is good for everyone, and we have an eye on fee compression. For a platform to win going forward, it needs to work on getting fee structures down, as well as harnessing the power of all-to-all liquidity.”

Rayner says, “The use of TRACE [the US post-trade pricing tape] helps with pricing data, but every platform has managed to come up with fairly decent intraday pricing tools.”

Understanding the interplay between a platform’s pricing is crucial, says Recordon, as there can be different spreads that a trader needs to keep a close eye on.

“In the States, pricing of the underlying benchmark for govies trading is a very smooth and automated process,” Recordon says. “That is not the case in Europe. We have to fight even on quotes. When we trade on spread, we need to ensure that the underlying quote is good. We receive VCONs [automated voice confirmations] and price up all our trades manually. A lot of people use process-negotiated trades (PNTs). We feel that banks could take advantage of people who only process electronically, because they are less focused on the underlying spot that they get, and so they might be taking out a few cents here or there. Occasionally, when I’ve tried to agree a price via PNT on a trade that I have agreed on spread, the underlying spot is often not great and we often have to pull the counterparty up on it, and get an improvement.”

The UK and European Union are both set to increase transparency levels through the introduction of consolidated tapes, while there are questions in the US when trades in large sizes are published.

Welsby says, “It is challenging in Europe to know where the mid-market is, but equally transparency can potentially end up worsening liquidity. If large blocks are going to get published straight away, people may stay away from trading blocks. We need to be careful that liquidity doesn’t decrease.”

Having gotten benchmark data to assess execution performance, the right analytics need to be applied in order to reflect liquidity, customised by market segment. “You want to be sure to focus on not only TCA results to the moment, but what that traders accomplishing in the long run,” says Coccoluto. “Leverage your traders’ expertise to customise how you how you take data from market nuances.”

This can be quite different between the US and Europe, Munro observes, with different segments of credit trading also presenting challenges.

“When Henderson – which had very limited dollar trading – merged with Janus we found the TCA benchmark used in Europe was not particularly effective for US, notably for high yield, and we now use a waterfall of benchmarks to ensure they are most effective for the region and the asset type,” he explains. “If you use CBBT in Europe you won’t necessarily use that in the US due to the way banks present prices on ALLQ so you may use TRACE and BMRK or another benchmark. You have to take TCA information according to what is appropriate for market, region and asset type.”

The decision tree in trading has to account for these elements, says Rayner, but by feeding this information back to the portfolio managers effectively, it can really improve the investment process, providing greater savings or alpha generating opportunities to end investors.

“Where the decision tree has changed is on the portfolio management side,” he says. “When handling inflows and outflows, historically a PM might have traded an outflow by picking a few items and selling larger amounts to take care of that liquidity with immediacy, now it could be selling a slice of a portfolio, and that affects the way we handle the ticket. On an inflow where there used to be more of an inclination to buy a CDX or ETF as a beta placeholder, one might now top up your entire portfolio. That has changed the decision tree before an order gets to the trading desk.”

Photos: www.richardhadley.net

©Markets Media Europe 2025