When market makers offer no bids for corporate bond trades, buy-side traders need to get creative.

Dealers are the main source of liquidity in the bond market, but this takes their investment management clients hostage when banks are reluctant to take or pay for risk. In 2022, as markets became highly directional, driven by redemptions and portfolio rebalancing, banks stepped back altogether from some trades.

“It used to be a matter of pride for market makers to provide a bid,” notes one buy-side trader, speaking on condition of anonymity.

While this is a justifiable commercial decision by the banks, asset managers need to find solutions to this liquidity drought.

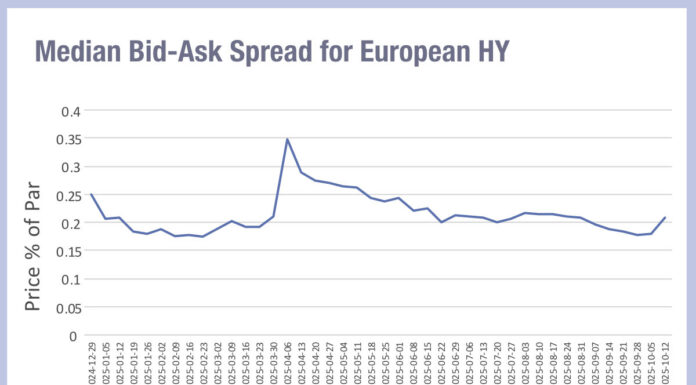

Trading platforms have reported volumes rise and fall as events, including the invasion of Ukraine, rocketing inflation and central bank responses have buffeted portfolios.

“It has definitely ebbed and flowed with comments from policymakers, and the geopolitical backdrop,” says Chioma Okoye, managing director for European institutional credit Tradeweb, noting that the impact of liquidity has been felt worse in European markets than in the US.

“The average execution level for fixed income trades, versus our mid- or composite price, has tripled from about -2 basis points in January to -6 basis points in July for European investment grade bonds,” she says. “By comparison, for US investment grade credit, the move has been about 1.6 times from about -1.5 basis points to -2.4 basis points versus the Tradeweb Ai-Price.”

Changes in market circumstances are one challenge for traders this year, but more extreme changes such as an absence of liquidity provision is harder to counter, argues Mike de Pass, global head of linear rates trading at Citadel Securities.

“If you have the ability to know what liquidity and volatility will look like, and you can adjust your trading, you can adjust your risk taking to be consistent with the level of volume and liquidity in the market,” he says. “The problem comes when liquidity in the market is unreliable, or market functioning completely breaks down.”

Alternative paths

Assessing how to find the other side to a trade has been made easier through the wide range of trading protocols that have been developed by trading platforms. These provide the capacity to manage two of the trade dynamics such as price, speed or market impact, usually with the trade-off of worsening another. For example, a request-for-quote (RFQ) in competition worsens market impact but helps price and speed. Portfolio trading is slower but improves market impact and price.

“Protocols meet clients’ needs in different ways and they switch between them, depending on the trading objective,” says Okoye. “Europe has seen single item RFQ usage increase relative to list RFQ over the past couple of months. If it is a list that needs trading, portfolio trading is being used to be able to get that certainty of execution, particularly in volatile periods.”

Although reports from some market operators recently have suggested that engagement with portfolio trading has plateaued, this may reflect the number of participants rather than the level of activity occurring.

“It’s definitely becoming more concentrated. In the beginning, there were probably over ten liquidity providers active in this space and now it’s less, but you’re still put in competition with three to four people,” says Ramon Baljé, head of fixed income at electronic market maker, Flow Traders. “Platforms like Tradeweb put lot of work and investment into pre-trade analytics for portfolio trading so clients can do a lot of work looking at overlap between exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and their portfolio, at statistics around the hit ratios and trade performance for individual liquidity providers, and then they get very good execution.”

Where there is disengagement it potentially reflects the inability of some market makers to handle the risks being generated by sophisticated client requests, made more challenging in volatile markets.

“We hear that some dealers are [stepping back from portfolio trading], and I think it is because some of these portfolios are getting more complex, with mixtures of different instruments, different currency instruments or both high yield and investment grade,” says Baljé. “Where nearly 10% of volumes are processed via portfolio trading banks want to get involved. However, portfolios are being priced aggressively, notably from ETF market makers. Some banks run a centralised risk book where positions, ETFs, credit default swaps, and index products are managed centrally and that allows them to price these portfolios.”

All-to-all trading models have also become more popular as traditional liquidity providers have proven unable to meet demand, including market operator MarketAxess’s Open Trading protocol.

“Open Trading penetration rates are up at 37% overall across our core products, and 53% in high yield,” says Rich Schiffman, head of Open Trading for MarketAxess. “That says something about dealer activity, relative to alternative liquidity provider activity. Maybe some of the main market makers are less active in August creating some more opportunity, but that’s a high number. It gives a sense of opportunities in the market.”

Fresh prices

In addition to these routes to liquidity are new price and liquidity makers, who are not constrained by the same pressures as traditional bank sales-trading desks.

“A theme we’ve been talking about for many years now is the shift towards alternative liquidity providers, opportunities for traditional buy-side firms to be involved in price making,” says Schiffman. “That reflects a lot of what we’ve seen so far this year, and in the improved numbers that we’re seeing on our platform.”

He notes that liquidity provision is becoming a primary source of getting liquidity in the market for some firms.

“Those firms that are good at it, commonly have a portfolio manager doing the trading so the process is seamless; they’re making their own calls,” Schiffman says. “For firms that have a more rigid PM/trader split, it’s not impossible, and those firms are certainly becoming price makers as well, but you can see where it’s more difficult, because a communication channel has to be open, and discretion determined for the trader before they execute an order. They’re trying to get better in the way that they operate, with benefits from the efficiencies of that order workflow while having the flexibility to be price makers.”

However, de Pass observes that there can be structural barriers to entry for new liquidity providers, and these may need to be addressed by regulators if alternative market makers are to support absent investment banking liquidity.

“The size of the Treasury market has tripled post global financial crisis, and the amount of balance sheet dedicated to intermediation has likely gone down,” he says. “There is a structural intermediation problem.”

This is also true in other sovereign markets which are smaller but demand the same level of rigour as the US Treasuries space.

“Looking at sovereign bond markets in Europe; to access any of the liquidity platforms you need a primary dealer,” he notes. “To become a primary dealer [and] there’s a big moat around the entire structure [of being a primary dealer] that makes it really difficult. These things are not inherently bad, the moat exists because you want liquidity providers that are committed to the market, but there is a balance. There’s no incentive at all for any new player to enter those markets. When we look at replicating [our dollar business] in EGBs, we would need to be a primary dealer in seven different countries with seven different regulations and seven different demands. It is not easy.”

With the cost of market making affected directly by capital adequacy regulations, and liquidity crises occurring in every bond market to some extent, it may be that authorities have to re-evaluate the impact of these rules.

©Markets Media Europe 2025