Stressed events – like the gilt market turmoil – are proving too much for the secondary markets to handle.

Behind closed doors, senior traders are concerned about the dysfunction seen in bond markets during stressed periods.

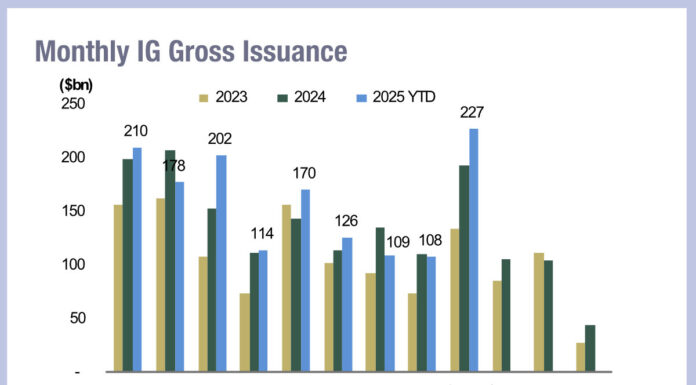

The US Treasury markets saw a withdrawal of liquidity provision during points in the March 2020 sell-off, and credit markets in 2022 – particularly in Europe – have seen similar concerns become more commonplace, and the US Federal Reserve Bank of New York has published indicators of stress in North American credit markets.

When stressors are added to the market – the war in Ukraine, the UK’s ‘mini-budget’ – or even the more commonplace such as interest rate movements, it exposes weaknesses in liquidity provision which could severely impact buy-side firms.

The greatest risk to a firm is an exposure to leverage. Not only did it sit behind the September 2022 gilt crisis, triggered by liability driven investment (LDI) strategies as they struggled to cover margin calls, it has historically triggered credit events at hedge fund Long Term Capital Management in 1998, Lehman Brothers in 2008 and nearly at insurer AIG in the same year – the latter averted only via government intervention – and the collapse of leveraged hedge fund Archegos in 2021.

“These episodes highlight the need to take into account the potential amplifying effect of poorly managed leverage, and to pay attention to non-banks’ behaviours which, particularly when aggregated, could lead to the emergence of systemic risk,” said Sarah Breeden, executive director, financial stability strategy and risk and member of the financial policy committee at the Bank of England, in a speech on 7 November 2022.

“Leverage is of course not the only cause of systemic vulnerability in the non-bank system – as we have seen with liquidity mismatch driving run dynamics in money market funds (MMFs) and open-ended funds (OEFs) during the [March 2020] dash for cash,” she continued. “But it is important where any form of leverage is core to a non-bank’s business and trading strategy. Indeed what happened to LDI funds is just the latest example of poorly managed non-bank leverage throwing a large rock into the pool of financial stability.”

The crisis in UK gilts is worth exploring because it exemplifies several characteristics of market dysfunction today.

What happened?

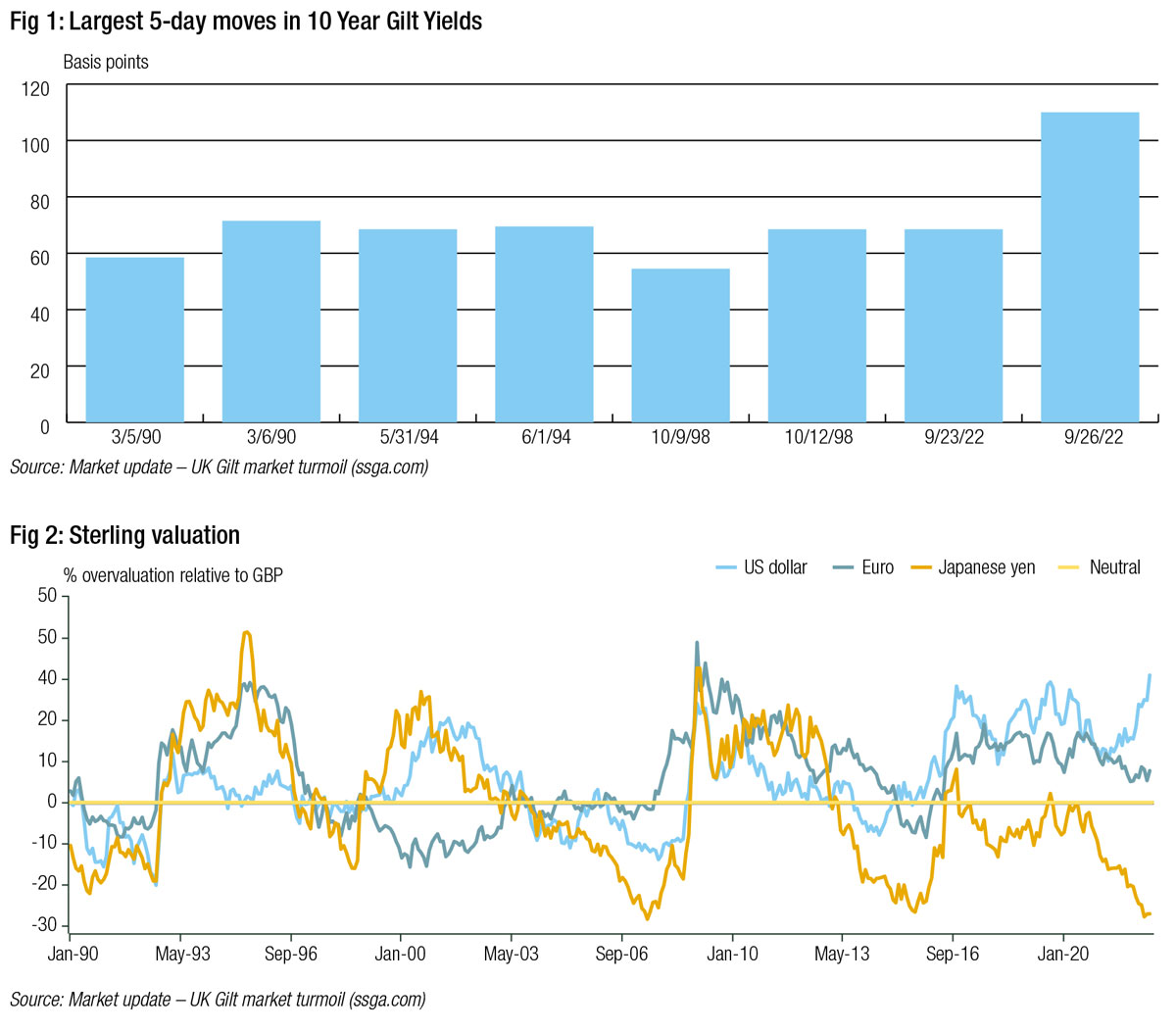

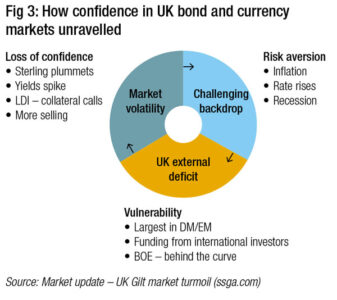

At a practical level, the UK Government as of late September, suggested it would use a huge amount of debt issuance to support a massive amount of spending. That triggered a sale of the pound leading it to fall in value. The market expected rates would have to rise very rapidly to fund the borrowing and the market began selling existing gilts as prices fell and yields (the coupon as a percentage of the price) rose.

“The rise in yields in late September – 130 basis points in the 30-year nominal yield in just a few days – caused a significant fall in the net asset value of these leveraged LDI funds, meaning their leverage increased significantly,” said Breeden. And that created a need urgently to de-lever to prevent insolvency and to meet increasing margin calls.”

“The rise in yields in late September – 130 basis points in the 30-year nominal yield in just a few days – caused a significant fall in the net asset value of these leveraged LDI funds, meaning their leverage increased significantly,” said Breeden. And that created a need urgently to de-lever to prevent insolvency and to meet increasing margin calls.”

As one senior investment professional explains, “In those few days at the end of September it was difficult to find a functioning gilt market. The speed of moves that we were seeing in yields had the effect of discouraging participants from engaging with the market and when that happens, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. What we’ve learned since those few, very dramatic days, was that there was a lot of forced selling. It was difficult to find prices, it was difficult to execute any sort of business, it really was a complete breakdown of the market.”

An analysis of the UK LDI crisis published by asset manager State Street Global Advisors, reported, “The gilt market itself practically ceased to function properly as the scale of unfunded policy action in the government’s ‘mini budget’ was digested. The hit to sentiment, in what was an already jittery bond market, gave rise to a negative feedback loop that pushed the market to extremes and certain pension schemes into a liquidity squeeze.”

Firm that were using derivatives to support pension portfolios and held gilts in their portfolios suddenly had to meet increasing margin calls by selling their gilts for cash as they fell in value, and into a market where there were few buyers.

“These [LDI] investors, with over £1.5 trillion in assets, dominate the long end of the gilt market,” noted SSGA. “They had to act quickly to meet immediate, and significant, calls for additional collateral to cover margin calls. They were faced with difficult choices: sell assets, deleverage at market extremes, or seek cash contributions from their parent companies.

Ultimately the Bank of England had to step in as a buyer of last resort, which also effectively meant it was working against the government’s policy.

The lessons for traders in this market

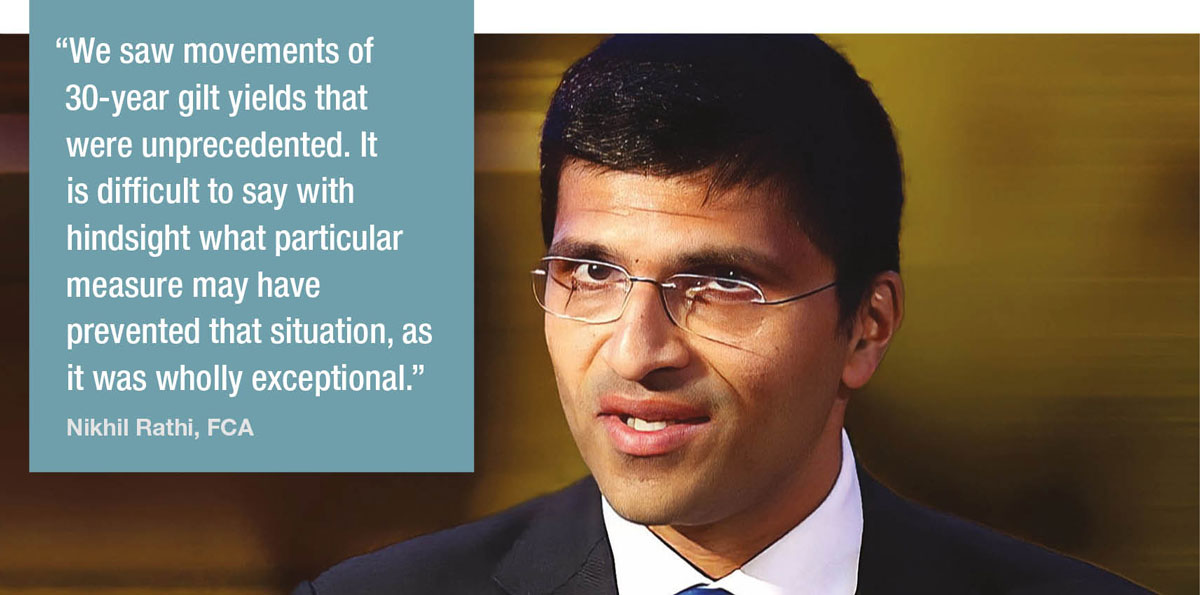

The events seen in September 2022 gilt markets were exceptional as Nikhil Rathi, CEO of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) observed when giving evidence to the Treasury Committee after the event.

“We saw movements of 30-year gilt yields that were unprecedented,” he said. “We had never seen those in the history of the gilt market; they were twice as large as March 2020 and three times as large as any historical norm. It was beyond anything that any of us had experienced before in terms of price movements, and that led to the risk of a self-reinforcing spiral as some of that leverage was being unwound, and as margin calls were being made for derivatives as collateral needed to be accessed. It is difficult to say with hindsight what particular measure may have prevented that situation, as it was wholly exceptional.”

Certainly, this was a situation beyond the market making dynamic. Nevertheless, trading desks need to consider if lessons can be found. Nobody wants to be a forced seller, but any funds carrying leverage must be aware of the risks this holds, and the trading desk needs to be conscious of events that could trigger forced selling activity in order to acquire cash, to meet margin calls.

Traders from LDI providers who have spoken to The DESK on condition of anonymity, identify that cutting information leakage and trading in large size wherever possible was the key objective.

One simple solution which bypasses trading, and one expected to be used by many funds going forwards, is to hold more cash instead of investing it in assets. In the events of the gilt market crisis, at least one pension fund – J Sainsbury – put a loan facility in place to access £500 million in cash, which it reportedly did not have to use.

The wider perspective

The US corporate bond market has also seen the Fed’s emergency direct bond buying programme, the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), used in times of liquidity stress.

Liquidity is also being challenged in more normal markets, and the withdrawal of dealer participation leads to an increasing likelihood of central bank intervention. This begs the question of whether bond markets can function fully without that intervention.

“How does direct bond buying impact market structure innovation?” asked Chris White, CEO of pricing data provider, BondCliq. “The intention of the SMCCF, as well as other central bank fixed income asset purchase programmes, is to stabilise markets by ‘adding liquidity.’ However, a key feature of direct bond buying is that only broker-dealers are able to trade with the central bank. Therefore, central banks are not acting as the buyer of last resort to the entire market, instead, they have been functioning as risk warehouses for market makers. By allowing broker-dealers to dump their risk, at a profit, central banks have reduced the urgency to innovate.”

The fundamental causes of illiquidity cannot be managed by a single trading desk. They are largely structural. However, awareness of the challenges created must be considered and planned for by heads of trading as they seek to pre-empt the effect on their own portfolios.

©Markets Media Europe 2025