The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has had its rule, that would have defined electronic market makers as ‘dealers’, vacated in case tried by Reed O’Connor, a judge in the US District Court for the Northern District of Texas. SEC chair Gary Gensler announced his resignation on the same day.

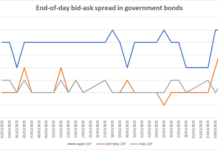

Non-dealer market makers have been allowed to use interdealer US treasury markets for over a decade, trading on electronic platforms such as Brokertec. The reason that ‘interdealer’ electronic trading platforms gave the same access to non-dealer trading firms as they do dealers, has never been given.

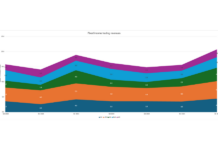

As a joint-agency report noted in 2015, “Bank-dealer activity in the ‘interdealer’ market now accounts for well under half of the trading and quoting activity, a significantly smaller share of market intermediation than in the past, perhaps reflecting increasing costs and competitive pressures associated with market-making activities in the Treasury market.”

Concerns have been raised about the participation of non-dealer liquidity providers in markets over the last decade, notably after a 2014 ‘flash crash’, as they lack risk capital to use as a buffer against taking on risk positions. The SEC rule was seen by some as an effort to balance this with bank dealers.

However, in the decade since market structure has shifted dramatically, with many big banks trading bilaterally with electronic market makers rather than via electronic platforms.

The National Association of Private Fund Managers, Alternative Investment Management Association Ltd, and Managed Funds Association had filed the suit in March 2024 against the SEC, which had sought to further define the term ‘’as a part of a regular business’’ in the Exchange Act’s definition of ‘dealer’ and ‘government securities dealer’ in connection with certain liquidity providers, which would have brought them into the definition of a dealer.

In his final opinion, O’Connor wrote, “The plaintiffs do not dispute that the phrase “as a part of a regular business” is a “technical, trade, . . . [or] other term[]” used in the Act’s definition of “dealer.” The SEC’s new definition in the Dealer Rule, however, is not “consistent[] with the provisions and purposes of” the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

The Exchange Act’s “dealer” definition is central to this case. Section 3(a)(5) of the Exchange Act defines a “dealer” as “any person engaged in the business of buying and selling securities . . . for such person’s own account through a broker or otherwise.”

The definition contains a carve-out, commonly known as the “trader exception,” for persons who buy and sell securities for their own accounts “but not as a part of a regular business.” Importantly, the Exchange Act also defines “broker,” a related statutory term, as “any person engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others.”

The Commission does not distinguish between brokers and dealers for registration purposes as firms can only register as “a broker-dealer,” not as a broker or dealer independently, the court noted.

“Thus, under the statutory scheme enacted in 1934 to regulate the finance industry, Congress differentiated brokers and dealers based on how one engaged in the transactions of securities, be that for the account of others—a broker—or for one’s own account—a dealer. And by the above-mentioned registration as a ‘broker-dealer,’ the Commission recognises this parallel,” writes O’Connor.

He found that “’The business of buying and selling securities’ when Congress passed the statute was to effect ‘an order . . . for a customer.’ Congress did not address all businesses of buying and selling securities. As [SEC] Commissioner Peirce put it, ‘[t]his rule turns traders, many of whom are customers, into dealers. Doing so runs counter to the statute, as the Commission and market participants have read it for decades.’” The Court noted that is agreed with Commissioner Peirce.

Summing up he wrote, “The Commission has exceeded its statutory authority in adopting the Final Rule. Under Section 706 of the APA, when a court holds that an agency rule violates the APA, it may—‘hold unlawful and set aside’ [the] agency action. Because the promulgation of the Final Rule was unauthorised, no part of it can stand.”

©Markets Media Europe 2025