New fixed income committee sees pushback on structural approach to resolving credit market challenges. David Wigan reports.

As European fixed income market participants get their teeth into the new trading and transparency requirements under MiFID II, US regulators have launched an initiative to consider how to tackle some of the issues facing bond markets, and particularly corporate bonds.

In November the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) established the Fixed Income Market Structure Advisory Committee (FIMSAC) with the aim of generating new ideas to enhance market efficiency and resilience in corporate and municipal bond markets. However, in the wake of its first meeting, market participants are betting the committee will favour a softly, softly approach over Europe’s prescriptive solution, MiFID II.

“Certainly, there is a question over whether the SEC is thinking about moving the US closer to MiFID or has a lesser initial ambition which is to find out more about the issues impacting the market and what participants think of them,” says Larry Tabb, head of research at Tabb Group and a member the Committee. “My instinct, and I think that of most people who are associated with the committee at present, is that it’s the latter – that we are at an early stage and the SEC’s initial priority is to get an understanding of how the market feels it is progressing.”

Europe has engaged in a ‘big-bang’ approach to making European securities markets safer and more transparent. It has engendered sweeping new requirements for trading on venues across asset classes, alongside pre- and post-trade transparency requirements that aim to guarantee that price discovery and market positioning are not impaired in sometimes relatively illiquid markets. While there are exemptions, particularly for smaller trades, the rules are set to have a powerful impact on liquidity provision as everybody keeps an eye on what rivals are doing.

Europe has engaged in a ‘big-bang’ approach to making European securities markets safer and more transparent. It has engendered sweeping new requirements for trading on venues across asset classes, alongside pre- and post-trade transparency requirements that aim to guarantee that price discovery and market positioning are not impaired in sometimes relatively illiquid markets. While there are exemptions, particularly for smaller trades, the rules are set to have a powerful impact on liquidity provision as everybody keeps an eye on what rivals are doing.

The US has its own transparency code, through the FINRA-operated Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE), into which broker-dealers feed corporate bond and, since July 2017, Treasury transactions. All trades are reported, a slightly more onerous requirement than in Europe, but there is no pre-trade reporting or disclosure, a gap compared to European requirements that raises a question over whether the SEC may seek to equalise.

Industry guides the committee

SEC spokesperson Judith Burns declined to comment on future plans. However, evidence of the SEC’s approach was on display at the Committee’s inaugural meeting on 8 January 2018, in which a range of market participants were invited to take part in panels to discuss liquidity in the corporate bond market, a perennial and much discussed issue after dealer balance sheets shrunk in response to heavier capital requirements and restrictions on prop trading imposed after the financial crisis.

Michael Heaney, committee chair and board member of Legal and General Investment Management Americas and TP-ICAP, picked three broad topics to address via subcommittees: modernisation including electronification; fixed income ETFs, open ended mutual funds and concentration effects; and transparency.

However, the committee was warned off looking for equity-like fixes – such as Reg NMS – which could impose workflows on corporate bonds. Speaking at the meeting, Sonali Theisen, global head of market structure and data strategy at Citi, set out some of the key characteristics of the corporate bond market that distinguish it from equities.

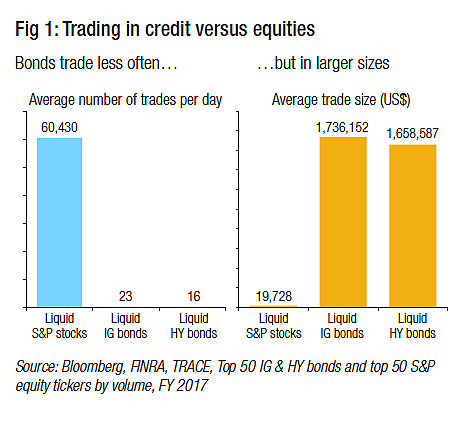

For example, she noted that the number of unique securities in the S&P 500 was 11,990 for bonds, compared with 500 for equities, and that while liquid S&P stocks trade more than 60,000 times a day, liquid investment grade bonds trade around 23 times on average.

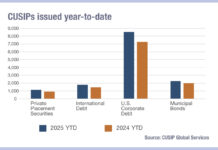

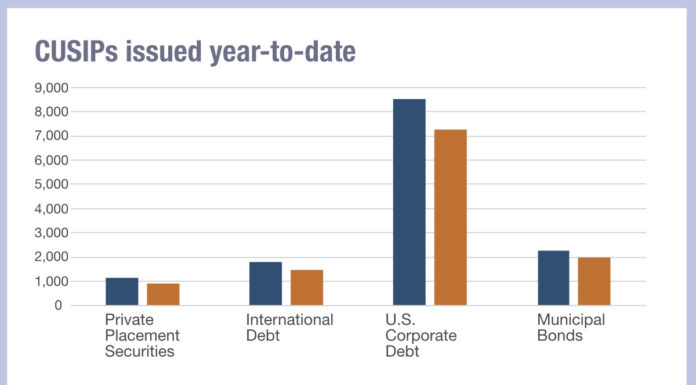

Bonds also trade in much larger sizes, Theisen showed, with the average trade size for investment grade (IG) bonds coming in at around US$1,736,000 in 2017, compared with an average equity trade size of around US$20,000. In addition, bond liquidity is challenged by a lack of standardisation (see Fig 1).

The starkly different characteristics of the bond markets create a different liquidity picture to equities, with very little by way of sustained two-way flow and liquidity takers much less likely to manage their own execution risk. And as the liquidity challenge has intensified, the market has begun to change shape, with for example less pension funds, insurance companies and banks/brokers taking part. In part their place has been taken by foreign investors and mutual funds, who accounted for 80 percent of the market in 2017 compared with 50 percent in 2007. However, there has also been an absolute drop in buying volumes, based on Q4 numbers, with around US$7 billion of purchases in 2017, compared with US$11 billion in 2007.

How to move forward

For the SEC the shifting dynamics raises some interesting questions. Should it intervene to promote liquidity? How would that intervention look (should it perhaps mimic MiFID II?) and would it be desirable or effective?

At the meeting, Richie Prager, head of Trading, Liquidity and Investments Platform, at BlackRock said, “We would like to see some pilot that addressed better calibration around trade size that would encourage more transactions.”

Furthermore, former commissioner Mary Jo White had said during the planning phase for the committee in 2016, that it would be established to address disruptive trading practices, amongst other areas. Appetite for immediate action is likely to be tempered by the regulatory climate, with a move to reduce not increase regulation, and a clear need to understand the complexities.

“Certainly the SEC has the ability to do something to address the liquidity issue, for example by loosening the requirements around trade reporting (to encourage dealers to provide more liquidity) or prescribing new trading protocols, but I would say for the moment they are more focused on doing their research and making sure they fully understand the nature of the issue,” said Kevin McPartland, head of market structure and technology research at Greenwich Associates.

“There are also issues of public perception to consider – for example extending the window for trade reporting might be seen as making life easier for market participants, which may not play well publicly.”

From the perspective of the buy side, which is most impacted by the liquidity crunch, there is also little apparent expectation of a European-style approach.

“I don’t think the SEC is looking to introduce a US version of MiFID II, with a prescriptive solution for transparency, but they do want to know how the market has made progress over the past two or three years,” says James Switzer, head of credit trading at AllianceBernstein, who presented to the committee at its inaugural meeting.

“For me, if we want liquidity improved we need to see better pre-trade transparency, and that might be through a tech solution, though none are currently knocking the cover off the ball, or a more advanced way of working, and on that front we have seen the market make some innovations over the recent period.”

The current way ahead

The market is not sitting still. There is a bustling growth of ideas to fuel insight and trading models. Pre-trade transparency can mean improving insight into market conditions, using algorithms to build a view across venues, to grow confidence in terms of pricing and best execution, and for the buyside to be less reliant on being shepherded by the buy side, Switzer said.

Electronic trading is also growing in importance – nearly 85% of investment grade investors use electronic trading, which now accounts for 20% of overall trading volume on a notional basis, according to a Q4 2017 Greenwich Associates report, compared with just 69% in 2013, and electronic platforms have become more adept at promoting liquidity through TCA and data products.

In addition, firms are changing the way they take on and relinquish risk. Whereas previously, for example, asset managers that wished to sell bonds would literally comb their portfolios for suitable securities and then call their dealers, now they might instead spare the dealer the pain by doing a much larger size of more diversified risk.

“Instead of selling, say US$50 million of specific bonds we might now sell a US$150 million basket comprising 75 line items of US$2 million each, which they can more easily hedge with total return swaps or ETFs,” says Switzer. “So we still sell beta but through a different approach.”

In launching the fixed income initiative in November, Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Jay Clayton said the SEC would wait to see how MiFID plays out in Europe before implementing tougher rules in the US. However, market conditions may require it to make a faster decision.

A multi-year bull market in credit has kept money flowing in, an easy environment in which to get complacent. If, or when, the cycle turns, there may be a rush for the exit, stretching the market’s limited liquidity resources to the limit.

“I think the SEC certainly would be worried about the prospect of an unruly sell off,” said Tabb. “That may be one reason they have chosen to look now and to try to understand what might happen in that scenario. It’s very much learning mode for the SEC, but of course that could change.”

©Markets Media Europe 2025