If funds are not given daily liquidity by the market, can they support daily redemptions for clients? Chris Hall reports.

If funds are not given daily liquidity by the market, can they support daily redemptions for clients? Chris Hall reports.

When pandemic-fuelled panic hit the markets earlier this year, investors’ dash for cash left institutional dealers to mop up the mess. According to the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), redemptions from bond funds “reached record highs in March, resulting in outflows of 4% of their net asset value”. The outflows forced fixed-income desks to try to offload bonds in markets where buyers were scarcer than a handshake in a lockdown. In a once-in-a-lifetime crisis, the risks of selling bonds that barely trade once a month to make good on commitments to daily dealing can be severe, and possibly systemic.

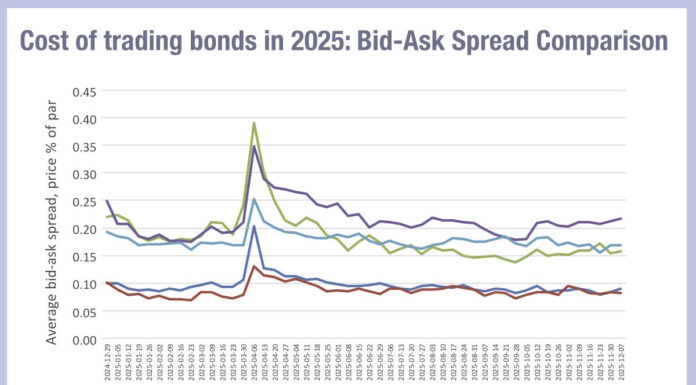

For some, it was time for the pretence to stop. Retail and institutional investors demand instant redemptions from mutual funds, but liquidity in many underlying bond markets does not support daily dealing, especially since Basel III forced banks and brokers to slash inventory levels.

Speaking in June, AllianceBernstein CEO Seth Bernstein said March’s liquidity crunch showed the bond markets had not yet settled on a stable market structure in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. Many fixed-income instruments remain highly illiquid, despite the emergence of all-to-all trading protocols. Bernstein advocated for a “daily pricing but periodic dealing model” in fixed-income mutual funds, due to the difficulties treating all customers fairly in the event of strong redemption demands.

Speaking in June, AllianceBernstein CEO Seth Bernstein said March’s liquidity crunch showed the bond markets had not yet settled on a stable market structure in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. Many fixed-income instruments remain highly illiquid, despite the emergence of all-to-all trading protocols. Bernstein advocated for a “daily pricing but periodic dealing model” in fixed-income mutual funds, due to the difficulties treating all customers fairly in the event of strong redemption demands.

“Our clients would be much better off having interval funds or something that deals in a pre-determined way so that we can manage liquidity more appropriately,” he said, arguing that investors in long-term fixed income funds did not strictly require daily liquidity. “I don’t see any silver bullet to the market structure deficiencies, so that sets a premium on portfolio managers to be much more disciplined about liquidity and how they manage their portfolio,” said Bernstein.

Conceived in the US in the early 1990s, interval funds offer only periodic redemptions, allowing portfolio managers the certainty to hold a higher proportion of illiquid bonds. Initially, interval funds allowed investors to submit redemption orders until the day before a specified buy-back widow closed, but the tendency of clients to wait until the 11th hour left trading desks struggling to handle demand, especially in stressed market conditions.

Funds then imposed irrevocable orders and longer lead times, i.e. 60 to 90 days, giving investors less flexibility. Already expensive, increased rigidity further reduced their appeal. Morningstar estimated they accounted for just 0.06% of total US fund assets in 2018. More recently, investor demand for diversification in long-term product offerings has reignited interest in the sector. In response, the Investment Company Institute is currently updating a white paper, ‘Interval Funds: Operational Challenges and the Industry’s Way Forward’ aimed at tackling the operational and distribution challenges of offering interval funds and other hybrid structures. Further, European trade associations are engaging with members on their potential to address the liquidity issues exposed in March.

Although their scale might be unprecedented, Q1’s liquidity challenges did not catch the industry entirely off guard. The topic has risen up the agenda both due to Basel III’s impact on market making and the pursuit of higher yield in the era of low rates and quantitative easing. High-profile cases such as Woodford Equity Income have reminded managers and investors of liquidity risks beyond bonds.

Regulators have responded. In 2018, the Securities and Exchange Commission provided updated guidance “to promote stronger and more effective liquidity management” at open-ended funds, including a toughening of rules that require funds to hold no more than 15% in illiquid assets without applying for exemption. The rules followed the failure of Third Avenue Focused Credit Fund in December 2015, which collapsed under the weight of heavy redemption demands.

In Europe, ESMA’s recent introduction of Liquidity Stress Tests builds on Financial Stability Board recommendations. And oversight intensified as outflows drained bond funds, according to Arthur Carabia, director of market practice and regulatory policy at the International Capital Market Association (ICMA).

“In March and April, there was a constant dialogue between fund managers, local regulators and ESMA to monitor the liquidity profiles of funds,” he says, asserting that the use of liquidity management tools (LTMs) helped to absorb redemption shocks and limit the impact on asset prices. LTMs often refer to the temporary suspension of redemptions, which some funds enacted in March to re-establish valuations, others for liquidity reasons. But it also includes anti-dilution levies and swing pricing, designed to encourage investors to stay put, essentially by adjusting the NAV to share increased transaction costs with those that choose to redeem.

Relatively few European funds resorted to LMTs. According to ESMA, around 200 EU and UK funds out of 600,000 temporarily suspended redemptions between mid-March and May, with UCITS worth Ä22 billion adopting suspensions by-end March. ICMA estimates this includes 30 bond funds with Ä11 billion AUM, a fraction of the Ä17.7 trillion assets of the European investment fund industry. Although he insists the crisis demonstrated the resilience of bond funds, Carabia says it alerted regulators to the need to offer more support

“This crisis has accelerated the adoption of LMT tools in Member States where they were not yet available, e.g. Germany. The ability of funds to deploy these tools across EU jurisdictions will be beneficial in managing future redemption pressures,” he said, but stopped short of calling for EU-wide regulation.

As in the US, European rules call on funds to manage liquidity in line with the needs of client. This is less a problem for institutional funds, but retail funds have a less clear view. Whereas institutional investors regularly engage with managers on their intentions, modelling retail behaviour is much harder because fund flow and investor data is held by intermediaries. To support liquidity risk management, ICMA is calling for data on investor profiles and shares held by different categories of underlying investors to be available to fund managers on a “mandatory and free of charge” basis.

Although Bernstein says portfolio managers need to be more disciplined about liquidity, Jean-Philippe Blua, head of investment risk and performance attribution at BlueBay Asset Management, says flexibility is paramount, implying LTMs should be a last resort.

In a prescient blog published last year, Blua commended a quantitative liquidity management framework based on liquidity scoring, stress-testing, concentration guidelines and constant vigilance, supplemented by qualitative insights. The extent of the March’s downward price spiral rendered quant models all but useless, says Blua, explaining that market experience helped BlueBay to exit certain EM positions in Q1 before the stampede began. “Our quantitative indicators were not flagging these as a big risk in our portfolios, but as we saw the market start to sell off, we considered potential risks further down the line and warned portfolio managers that any stability in local currencies was probably only temporary.”

Typically, any bond fund portfolio is constructed to offer some element of flexibility. Even funds weighted strongly toward less-liquid bonds dilute their bond holdings with US Treasuries, derivatives and equities, to offset the impact of a redemption shock on the balance and performance of the fund.

The Q1 redemption shock may not be repeated soon, but it will not be forgotten. ESMA’s traffic-light risk assessment still places the asset management sector on red alert, and the regulator’s latest risks report highlights the vulnerability of bond funds containing more illiquid instruments to shocks from other markets. Further, the suspension of redemptions by eight France-domiciled funds managed H20 Asset Management at the end of August shows liquidity remains a key risk.

Although many will be reassessing their liquidity management policies in light of March’s experience, Blua insists there should be room to take on liquidity risk where justified.

“As a risk manager, I want to ensure that if we are willing to accept liquidity risk, there needs to be very strong symmetry with the upside and the level of conviction of the portfolio manager,” he says.

©The DESK 2020

©Markets Media Europe 2025