Portfolio managers have some very large events to consider, along with many more nuanced side-effects.

At the beginning of the year, rising inflation and interest rates were the main concerns of traders and investors. Fast forward to March and geopolitical risks have taken centre stage with Russia’s unexpected invasion of Ukraine. This has forced market participants to go back to their drawing boards to determine how portfolios should reflect the changing market dynamics.

Currently, analysts are crunching numbers, but events are moving at such a fast pace that it is difficult to predict the fallout. They are factoring in several scenarios such as the state of military action, sanctions, central bank reform and negotiations if they occur.

The one thing that is certain is that volatility will be a feature for the foreseeable future and as Stefan Kreuzkamp, chief investment officer at DWS, puts it, the world has entered a “new geopolitical chapter.” He notes that after a first state of shock, markets are waiting for more clarity about the scope of Western sanctions as well as possible counter measures by Russia.

“Market dynamics to the downside might intensify if certain risk limits would be triggered with institutional investors,” he adds. “At the same time, historical experience tells us that such days are not a good time to sell either.”

Over the longer term, Kreuzkamp believes that Western sanctions against Russia and the ensuing supply constraints will keep inflation at loftier levels than expected. “The 10-year break-even inflation rate, as priced in German Bund yields, surpassed the 2%-mark last week,” he adds. “For economic growth, the forecast is less straightforward.

David Page, head of macro research at AXA Investment Managers shares this view. He believes that inflation will be a more persistent problem over the next two years. “We assume that oil and gas prices stay elevated for much longer driving headline inflation around 1 percentage point (pp) higher across key regions this year,” he adds. “Price rises will exacerbate real income squeezes, resulting in global GDP slowing to 3.6% this year from 4.0%, with output falling by 0.6 to 0.3pp in key economies.”

Central banks triggering market activity

The big question is what actions central banks will take if economies slow but prices keep rising. Before the conflict portfolios were positioned to reflect the more hawkish tone from the US and UK policymakers. Analysts at Goldman Sachs predicted that the US Federal Reserve would hike interest rates seven times this year to dampen down its record 7.5% inflation level but that now has been pared down to five. However, the Fed is pressing ahead later this month and delivering its first quarter-point interest rate increase since 2018.

The Bank of England (BoE) also had plans for more rate increases this year with last month seeing a 25-basis point jump to 0.50% to curtail its 30 year high 5.5% inflation rate. BoE policymaker Michael Saunders though said that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is likely to push Britain’s soaring inflation higher, but that it is too soon to determine the effect on monetary policy.

As for the European Central Bank (ECB), it had been sitting on the fence and views differed as to what action it would take to curtail its record 5.8% inflation spike. Its focus was on a possible wage price spiral but now ECB policymakers are arguing against any drastic shift in monetary policy until there is a clearer picture of how the crisis in Ukraine will affect the eurozone economy.

“In the shorter run, disruptions to the energy and commodity supply will weigh on growth,” says Carsten Brzeski global head of macro at ING adding “that it differs by country, but Europe gets nearly 40% of its natural gas and 25% of its oil from Russia.”

He adds, “Particularly in Europe, the risks of stagflation have increased. For the European Central Bank, but also for other central banks, this new situation is likely to slow down or delay policy normalisation. At the ECB’s meeting next week, any hints of rate rises are out of the question. We expect the ECB to avoid tying its hands in any direction; still announcing a taper, while not ruling out new easing of monetary policy if needed.”

Considered responses

Given recent events, it is no surprise that many investors and traders are not making any significant changes to their portfolios or strategies. There was a rush into classic safe haven assets such as government bonds, but they are expensive. In general, “credit is the primary candidate for repricing,” says Pascal Blanqué, chairman of the Amundi Institute. “Long-term inflationary expectations will be challenged by the Russian sequence – starting from rising energy prices, spreading into agricultural, global commodities – leading to rising bond volatility.”

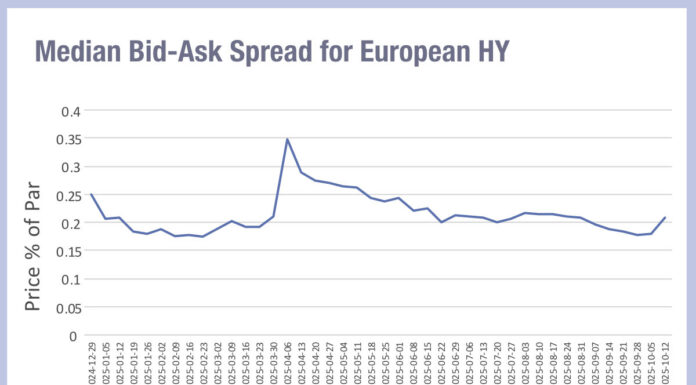

The conflict has cast a pall over high yield bonds which were favourite at the beginning of the year on the back of projected low default rates and robust corporate earnings. However, as Page points out, until recently, credit spreads had widened consistently with the ratio between high yield and investment grade falling. “This changed and now the HY/IG ratio is exhibiting a bearish decompression which suggests that credit is starting to price for a more material slowdown in growth and/or recession risk compared to simply reflecting a reset in risk premia, due to a more hawkish central bank outlook,” he adds.

Although high yield is still attractive and default rates are low, the future outlook will depend on economic growth and the impact of sanctions is still being assessed, according to Deborah Cohen Malka, partner and portfolio manager at AlbaCore Capital Group. “What we are seeing instead is a potential greater appetite for private credit,” she says. “People are looking to reduce execution risks. Despite the volatility, markets have been orderly, and we have not seen forced selling. However, liquidity has been thin on the back of the Russia/Ukraine situation, and we are also seeing a slowdown in issuance.”

There were already fewer corporate bonds to buy this year with analysts at S&P Global forecasting issuance to contract 2%. They attributed the downturn to tighter monetary policies but also China’s deleveraging policies, and the return to trend economic growth. Geopolitical risks were also on the list but no one predicting the Ukraine/Russia conflict.

What we do know, now

Figures from Refinitiv shows that conflict has already taken its toll on the market. The last week of February when the invasion started, companies around the globe raised around $60bn down from over $125bn in the prior full week and a year-to-date average of almost $100bn. Euro and US dollar denominated deals contributed less than half of the total.

The drop has been particularly marked for lower-rated, high-yield debt. Twitter was the only high-yield company in the world to come to market raising $1bn while several companies pulled their deals due to market volatility. This included nutrition products group Bellring as well as Spanish water management company FCC Aqualia which had planned to issue a two-part green bond last in February.

Overall, market participants, like everyone else are holding their breath. Volatility creates dispersion and prospects, but patience is advised. “In recent history, geopolitical crises have tended to be short-lived and after an initial sell-off they provide buying opportunities for investors,” says Pascal.

“It’s tempting to see a similar pattern in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which would explain why markets have been on a roller-coaster, with a fast recovery expected for any perceived positive development, after the initial negative shock when Russia launched its unexpected large-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February,” he says. “However, now is not the time to be complacent and buy too much into short-term news, until the picture of how the conflict is evolving becomes clearer.”

©Markets Media Europe 2022

©Markets Media Europe 2025