Reduced competition could lead to higher prices for buy-side bond traders.

The collapse of European brokerage houses is hitting buy-side trading desks in two ways. Firstly, in the shorter term, their ability to trade large blocks of bonds has reduced. Secondly, over the longer term, the reduction in trading partners could allow surviving sell-side firms to increase their margins.

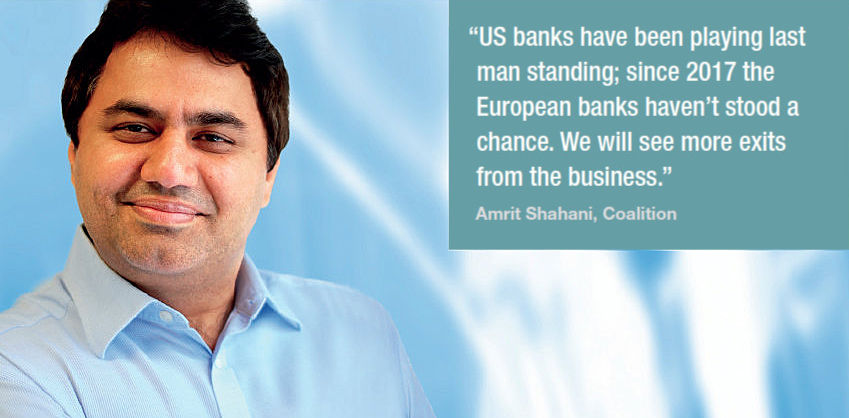

Amrit Shahani, research director at analyst firm Coalition, says, “US banks have been playing last man standing; since 2017 the European banks haven’t stood a chance. We will see more exits from the business. Eventually when the broker numbers reduce, they can crunch the market in terms of increasing margin.”

Amrit Shahani, research director at analyst firm Coalition, says, “US banks have been playing last man standing; since 2017 the European banks haven’t stood a chance. We will see more exits from the business. Eventually when the broker numbers reduce, they can crunch the market in terms of increasing margin.”

This is already felt on the street. The size of trades that are possible has fallen and greater support is clearly coming from Wall Street.

“Six years ago, the liquidity big European brokers provided to us was huge, taking £75 million blocks of corporate bonds off us in one clip,” says the head of trading at a major UK-based asset manager, who asked not to be named. “Nowadays that’s almost unthinkable, there are only two or three places you can go to try and do that now, and they are US banks.”

Experts believe the situation is unlikely to reverse itself, due to the structural changes which have triggered the decline in European firms. Shahani says these came about in two phases.

“The first phase was post-crisis in 2013-14 when European banks reduced their ‘micro’ businesses – securitisation and spread credit – and created bad banks to get rid of assets,” he says. “In the last five years those banks have been pulling back in FX, rates and commodities, the macro businesses. Of the top twelve banks, five are US and seven are European, but the European banks only have 38% of market share. Comparing the last five years, US banks share has increased from 40% to 55% in Europe Fixed income. The European banks are not really present in the US.”

The trigger for this second phase were changes made to capital adequacy rules by the Bank of International Settlements. It introduced new measures for assessing the reserves needed to manage leverage within banks, first published in 2014 and revised in 2016

Andrew Stimpson, research analyst, at Merrill Lynch International (MLI) says, “The big thing that happened was the introduction of a leverage ratio. On a European bank that was really devastating for the business they had at the time, and most of them are now adjusted.”

Andrew Stimpson, research analyst, at Merrill Lynch International (MLI) says, “The big thing that happened was the introduction of a leverage ratio. On a European bank that was really devastating for the business they had at the time, and most of them are now adjusted.”

These had a greater impact on European banks than US banks due to the different ways that they support capital raising and the historical restrictions that authorities placed upon them

“American banks always had some sort of leverage constraint on their businesses placed upon them by their regulator,” Stimpson said. “The European banks did not, so the European investment banks kind of grew up taking large, generally low risk trades onto their balance sheets.”

Apparent differences

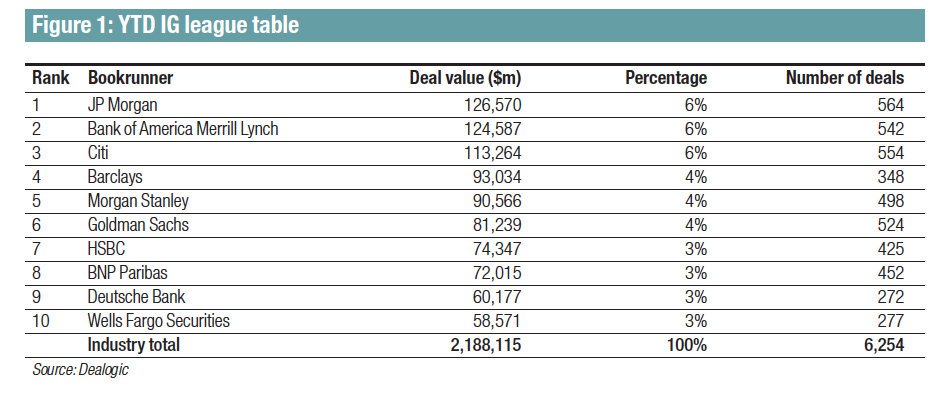

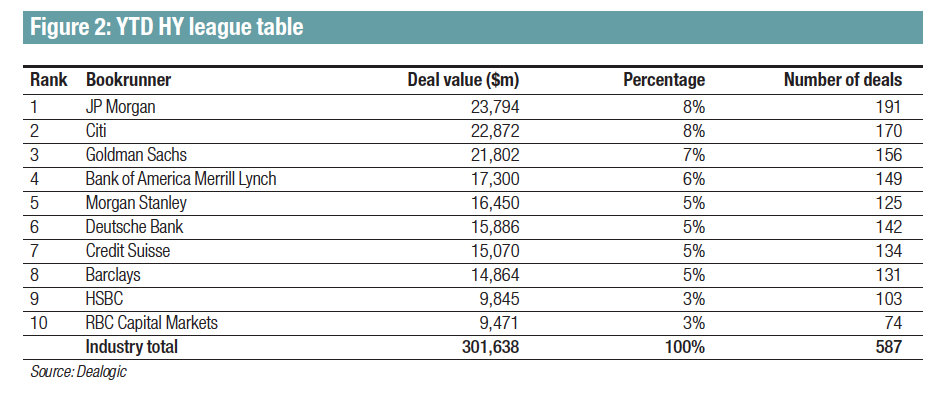

From a trading perspective, the effects are apparent within industry rankings. Primary market assessment from Dealogic put US brokers in four out of the top five positions for investment grade issuance (see Figure 1), while high yield issuance (see Figure 2) has an entirely US top five banks. Although trading volume in US IG credit has been rising year-on-year, based on data submitted to the TRACE system. Similar data for European trading is not available.

An assessment of broker performance in fixed income trading by Greenwich Associates sees Citi leading the pack, followed by Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan in second for market share, Barclays in fourth, and Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Merrill Lynch in fifth place.

Barclays is the only European firm to rank in the top five. It has also drawn praise from market participants as being committed to providing balance sheet where necessary to support them.

In the first half of 2019 it saw revenues from fixed income, currency and commodities (FICC) increase 14% to £1.87 billion against the same period in 2018 which, excluding its gains from the Tradeweb initial public offering, was pared back to a 3% gain which it attributed to rates and structured products trading.

By contrast the market leader, JP Morgan, saw an 8% decline in its Q1 2019 fixed income revenues to $3.7 billion against Q1 2018, and down 3% in Q2 2019 relative to Q2 2018 revenues. Second largest sell-side firm Citi saw its fixed income market revenues in Q1 increased 1% year on year to reach of $3.5 billion in Q1, then declined 4% in Q2 which the bank blamed on a challenging trading environment, particularly in rates.

In context, overall revenues in the space are falling; Coalition estimates that in 2017 fixed income delivered Ä76 billion of revenues across the industry, while for the full year 2018 it was Ä64 billion with several factors impacting that, from regulation to low yields.

Deep cuts

Given the importance of rates trading in major broker profitability, many European banks are hamstrung having backed out of the rates business in favour of credit, as a direct result of capital weighting.

“In the US you have risk weight constrained commercial banks, plus a leverage constrained investment bank,” says Stimpson. “Under one roof they are fairly balanced. In Europe we have leverage constrained commercial banks, and a leverage constrained investment bank. The European banks therefore needed vastly more capital to comply with leverage relative to the risk they were taking. That meant lower returns and unhappy shareholders.”

Their capacity to manage these capital weightings was tied to their historic capital reserves and appetite for leverage, but ultimately led them to cut rates rather than credit.

“If they had enough absolute capital they could just increase the amount of risk weighted assets,” Stimpson explains. “But they didn’t have enough capital, so what they had to do was shrink down their leverage constrained parts of their balance sheet, which is why we have seen most of the European banks exit their rates businesses.”

He notes this has led to cut both rates and prime in particular, because the risk weights on those businesses were approximately five per cent.

“Credit would be much higher, and the break-even risk weight if you are leverage constrained or risk weight constrained on a particular business is about 30 to 35%,” he says. “So if you have got something which only has a five per cent risk rate you need a lot more capital to cover the leverage requirement than you do for risk weight. If your risk weight is 100 per cent then you need a lot more capital to cover the risk capital requirement than the leverage requirement.”

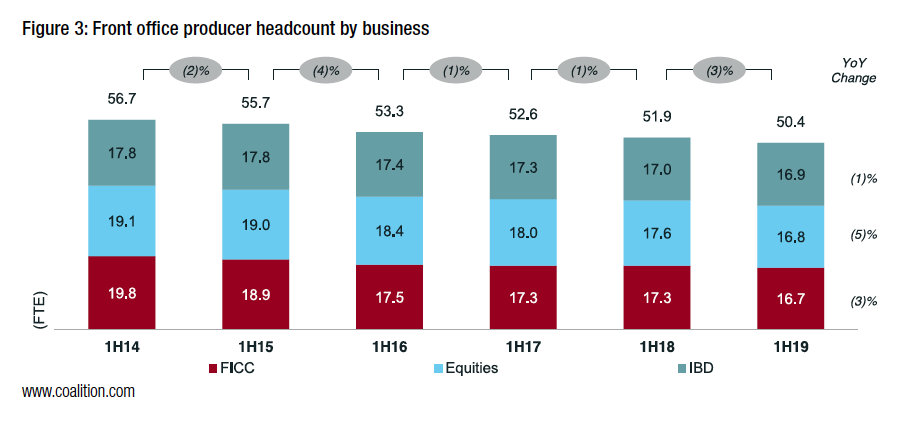

This pressure has led the European businesses to reduce their staffing and resources supporting the FICC sector, with Coalition seeing an industry-wide reduction of front office headcount of 15.6% in FICC business lines since 2014 (see Figure 3).

“Thematically what we had over the last year and a half was a rationalisation with European banks, many have clearly reduced their fixed income franchises while US banks have stayed put,” says Shahani. “They’ve engaged in housekeeping but net-net they’ve not reduced their headcount in the same way.”

Stimpson adds, “In most cases the banks have fixed their balance sheets at the cost of their P&L. Deutsche Bank in particular are at the sharper end of all this. The two Swiss banks have decreased the size of their investment banks to the level where they are smaller verses the overall group, but still pretty big even after all these adjustments. Barclays is still there but they are trying to trim costs.”

Looking ahead, BAML analysts see trading trends in 3Q to be either flat or lower in FICC, with a drop of around 2% year on year. Overall reduced risk taking could combine with an expectation of continued low rates to hurt banks’ secondary market bond trading into 2020, as activity remains subdued.

©The DESK 2019

©Markets Media Europe 2025