Buy- and sell-side veterans tell us the best practices which persuade brokers to take risk on their clients’ behalf.

Finding sell-side partners to take the other side of a trade is still a fundamental skill for buy-side traders. While banks may first consider the revenue that a client represents before they commit balance sheet to trading a block of bonds, their clients’ conduct impacts that decision.

“The reality is some people are platinum clients and some people are not platinum clients, so [balance sheet offered is] always going to vary,” says Andrew Munro, global head of fixed income trading at Janus Henderson. “How we treat the broker will reflect how we get looked after in the longer term. But in times of stress it is difficult to command balance sheet from counterparties and it’s part of our job to get it where we can.”

“The reality is some people are platinum clients and some people are not platinum clients, so [balance sheet offered is] always going to vary,” says Andrew Munro, global head of fixed income trading at Janus Henderson. “How we treat the broker will reflect how we get looked after in the longer term. But in times of stress it is difficult to command balance sheet from counterparties and it’s part of our job to get it where we can.”

Trading behaviour is being shaped by external factors. MiFID II’s best execution rules encourage traders to put their brokers in competition for orders. Increased use of electronic trading platforms is also reducing the level of interpersonal interaction in traders’ negotiations. Traders from both sides used to meet and speak more often, thereby building relationships and then using the trust they had established to transfer risk from one side to the other.

“Due to electronification there is an increased tendency to short-cut that relationship, taking the price on the screen and then expecting the sell-side trader to deal with that risk,” observes Stephane Malrait, head of market structure and innovation for financial markets at ING. “Just trading in the moment, based on the price on the screen, works for smaller faster trades but not for larger amounts or illiquid instruments.”

“Due to electronification there is an increased tendency to short-cut that relationship, taking the price on the screen and then expecting the sell-side trader to deal with that risk,” observes Stephane Malrait, head of market structure and innovation for financial markets at ING. “Just trading in the moment, based on the price on the screen, works for smaller faster trades but not for larger amounts or illiquid instruments.”

Consequently when fighting their peers for capital commitment, buy-side traders should be aware of how they present themselves to their counterparts, and the extent to which that can make their lives easier.

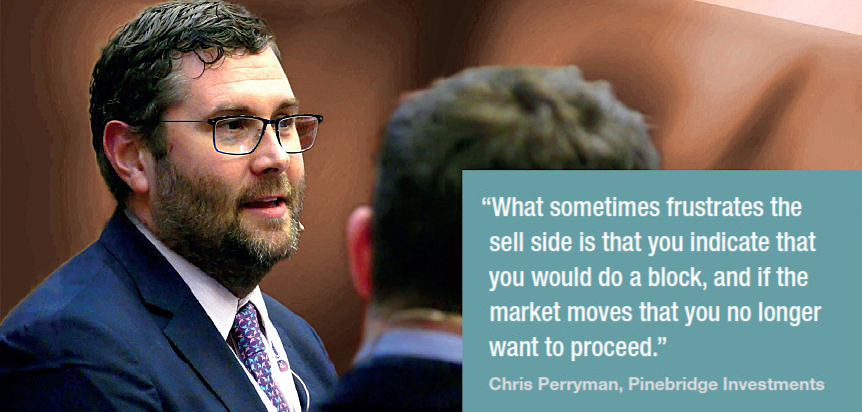

“You have to work on reputation on a continuous basis,” says Chris Perryman, senior vice president of Fixed Income Trading at Pinebridge Investments.

“You have to work on reputation on a continuous basis,” says Chris Perryman, senior vice president of Fixed Income Trading at Pinebridge Investments.

The other side

Banks and brokers have seen falling profitability from secondary market bond trading, a fall in liquidity within interdealer markets, and increased capital costs resulting from Basel III rules, which have increased the capital they need when holding risky assets such as corporate bonds. Collectively these factors have reduced the size of orders they can handle at any time.

Malrait says, “If you want to trade €200 million you may find a counterparty who has €100 million to absorb into their risk book but they may have to hedge the rest, either in the interdealer market or finding another client match, but it takes time. It is pretty rare to get a full match for a block trade.”

When taking risk on behalf of a client, a bank must ensure the rest of the street is not aware of the position it has taken on, or the market will move against it. Equally if it accepts fragments of a larger order it reduces the material value of taking that trade for a counterparty.

A global head of credit trading at a tier two investment bank, who asked not to be named, says, “If you are selling me paper [I need to know] you are not spraying the street with paper; if you are lifting me you are not lifting everybody else and by the same token you need to trust the sell side they will get things done for you, and not give partial trades unnecessarily.”

Buy-side firms understand the impact these behaviours can have and are cognisant of avoiding them where possible. However, the pre-trade liquidity discovery and price formation process requires that buy-side traders test the market in order to ascertain where the current price is in size. This probing has become more necessary as on-screen prices have become more removed from reality.

“The market has drifted over recent years to a place which is not entirely useful for credit, emerging markets, less liquid bonds that you can rely on the levels that you are seeing on screens,” says one head of fixed income trading at a UK-based asset manager. “Even if they are axes, runs or request-for-quote streams, they are not all entirely reliable.”

To limit information leakage during these processes, buy-side traders need to be cautious, testing the water with a smaller trade before committing to a block.

Malrait says, “The first reason a buy-side firm may not [give very specific information] is to minimise the market impact. They normally disclose enough to see if there is interest in that trade, but if they disclose too much to too many sell-side firms, leakage has already happened … The second reason is reduced transparency, due to the electronification of the market in FI, where the workflow does not allow the disclosure of intention.”

Where abuse occurs

The danger for brokers occurs when that discovery process is abused. This may be from the buy side, when the desk does not trade with those dealers which have provided a firm price.

“It dilutes transaction cost analysis because a lot of firms measure the hit ratios between their firms,” notes Malrait.

It can also be abused by the other banks, and asset managers can take a long-term view of counterparty behaviour, noting which banks – when put in competition – are likely to abuse the information they get.

One senior sell-side trader observes, “Buy-side firms need to be considerate of who they select, who they put in competition, and when the price moves following a selection of a counterparty.”

Equally in a scenario in which several channels are pursued to find price/liquidity, for example asking for prices by voice, over Bloomberg and Tradeweb at the same time, the trade is too exposed to the market.

“That is called a sweep of liquidity in FX and this has a negative impact on the market. The first dealer to accept the trade will see the market move away from them quickly, and their costs of hedging will be much worse than for the last dealer,” says Malrait.

Buy-side traders may also create problems if they are not committed to a trade which they have begun to set up.

“What sometimes frustrates the sell side is that you indicate that you would do a block, and if the market moves that you no longer want to proceed.” says Perryman.

Best behaviour

The buy- and sell-side relationship cannot be a short-term commitment; despite the reduced interaction between traders, it is important to maintain contact.

“If an asset manager comes to us on a day when the market is tanking and main spread is five wider and crossover is 20 wider and we have not seen them in a long time, our appetite to bid them paper in that market at an aggressive price will be smaller,” says a sell-side global head of credit trading. “We look at business consistently and constantly, not on a trade-by-trade basis.”

The buy-side desk should have a clear view of the price it wants to pay before engaging, and to understand if it is asking for a risk transfer price, or a risk price.

“If we are asking someone to facilitate a risk price, slippage is likely, so we have to consider what we are prepared to pay for, and to contextualise that,” says Perryman. “Are you getting out of the risk because it’s a relative value trade and therefore if both sides can move to the right price then it makes sense? Or are you moving out of it because of a change in credit view and outflow?”

Sell-side firms can help the process by using new electronic tools to support information distribution, they can prevent information leakage by shortening the time taken to complete a trade.

“The way to avoid [information leakage] is to distribute axes, and it can be done via the Neptune model via a secure network, where the information is reviewed in real time and stays confidential between firms,” notes Malrait.

Brokers can also encourage communication directly between their traders and their clients’ traders to provide valuable colour on their ability to engage with a particular order.

“We created the ‘triangle of trust’ with sales, traders and clients all communicating at the same time, and we encourage the traders to talk directly to the investors,” says one senior sell-side head trader. “If a trader cannot give a price they can explain why, also they feel they can give a few basis points when needed because there is respect, so the protocol is there.”

The greater the level of detail available to brokers on their performance within annual review processes, the more effectively they can support clients.

“The more detailed feedback on our performance the better, for example by maturity, and by size,” the same trader commented. “Also it is useful to know not only how much we traded but how much we were shown, how many brokers were being put in competition. If we traded Ä20 million that might look low, if it was 20% of what we were shown, in competition, it looks better, so context in analysis is important.”

These should include primary as well as secondary, but also a breakdown of activity on large blocks.

Our sell-side head of credit trading added the coda “I think we – the sell side – need to demonstrate we are worth trusting with larger trades foremost, we show we can do well and then we can ask for more business.”

©The DESK 2019

©Markets Media Europe 2025