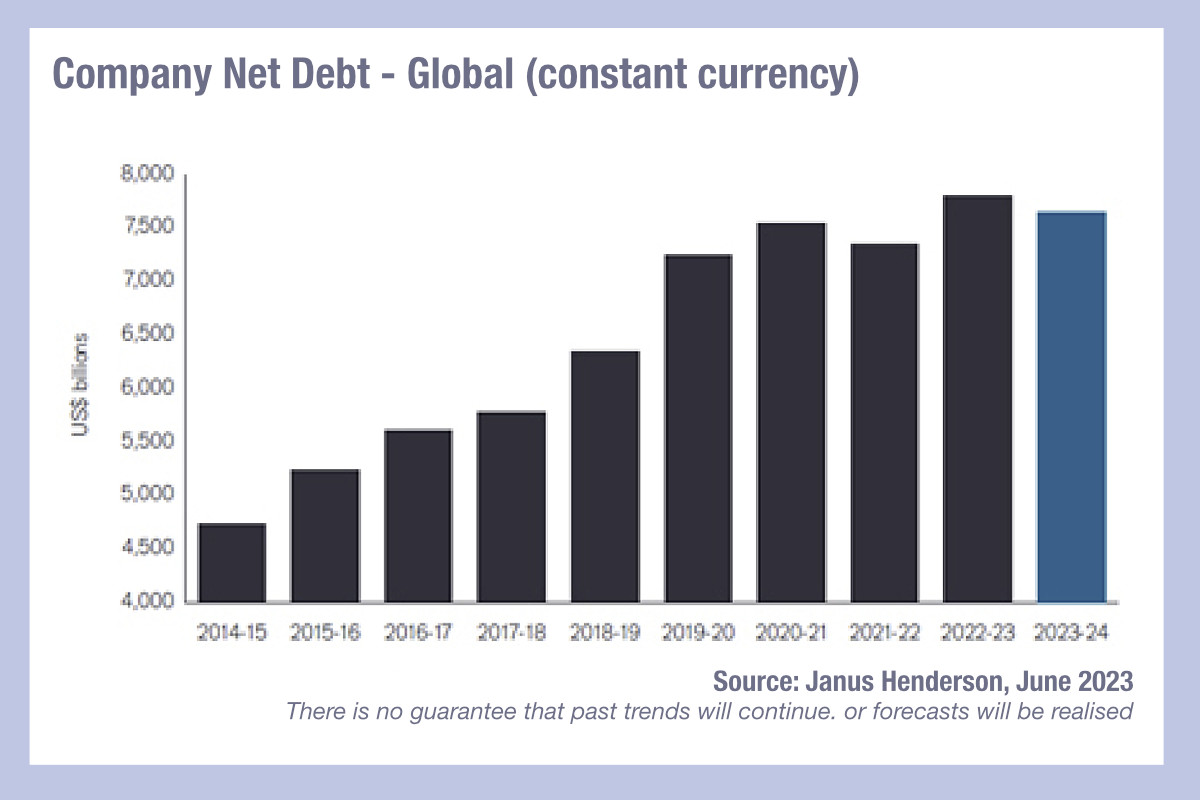

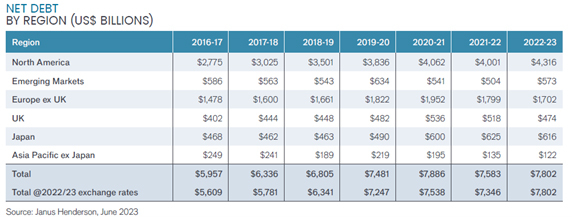

Companies around the world took on US$456 billion of net new debt in 2022/23, as of 31 March 2023, pushing the outstanding total up 6.2% on a constant-currency basis to a record US$7.80 trillion, according to the latest annual Janus Henderson Corporate Debt Index. This exceeded the 2020 peak, once movements in exchange rates were taken into account.

“The exact path for the global economy and corporate earnings may be very unclear, but the end of the rate-hike cycle and the return of ‘income’ mean there is a lot for corporate bond investors to be happy about,” wrote James Briggs and Michael Keough, fixed income portfolio managers at Janus Henderson.

Nevertheless, one fifth of the net-debt increase simply reflected companies such as Alphabet and Meta spending large cash reserves. Total debt, which excludes cash balances, inched ahead globally by just 3% on a constant-currency basis, around half the average pace of the last decade. Higher interest rates have begun to slow appetite to borrow, but have not yet made a significant impact on the interest costs faced by most large companies.

Verizon, the US telecoms company, became the most indebted non-financial company in the world in 2022/23 for the first time. Google’s owner Alphabet remained the most cash-rich company, according to Janus Henderson.

Global pre-tax profits, excluding financials, rose 13.6% to a record US$3.62 trillion in 2022/23, though the improvement was heavily concentrated. Nine tenths of the US$433 billion constant-currency increase in profit was delivered by the world’s oil producers. A number of sectors, including telecoms, media and mining saw lower profits year-on-year. Taken altogether, higher global profit boosted equity capital, and this meant the global debt/equity level, an important measure of debt sustainability, held steady at 49% year-on-year, despite increased borrowing.

Cash flow, which takes into account factors like investment and working capital, did not follow profits higher in 2022/23, however, dipping by 3% from record 2021/22 highs. Despite lower cash flow, companies distributed a record US$2.1 trillion in dividends and share buybacks, up from US$1.7 trillion the year before, and bridged the gap with higher borrowing or by running down cash piles.

Many large companies finance their debts with bonds that have fixed interest rates (coupons), and this is delaying the impact of higher interest rates – only about one eighth of bonds are refinanced each year, the portfolio managers said.

The amount spent on interest only rose 5.3% on a constant-currency basis in 2022/23 which was significantly less than the increase in global interest rates, and interest consumed a record low 9.2% of profits. There is significant regional variation. US companies rely more on bond financing and saw no increase in interest costs, but those in Europe, where variable-rate loans arranged by banks are common, interest costs rose by a sixth.

The median, or typical, yield on investment-grade bonds was 4.9% by May, up from 4.1% a year ago and 1.7% in 2021. This presents opportunities for bond investors to lock into higher income and it raises the prospect of capital gains as the interest rates cycle moves from increases to cuts in 2024.

The global economy is slowing as higher interest rates exert pressure on demand and on corporate profits. Higher borrowing costs and slower economic activity mean companies will look to repay some of their debts, though there will be significant variation between different sectors and between the strongest and weakest companies. Net debt is likely to fall less than total debt as cash-rich companies continue to reduce their cash piles. Overall Janus Henderson expects net debt to decline by 1.9% this year, falling to US$7.65 trillion.

Briggs and Keough explained, “Debt levels may have risen but they are very well supported, and the global economy has remained remarkably resilient. This resilience and the extraordinarily high levels of profitability companies have enjoyed in the last two years reflect vast sums of government deficit spending and central bank liquidity stimulus during the pandemic. The surge in interest rates needed to quell the resulting inflation is succeeding in most parts of the world, but it is not at all clear when and to what extent the economy will suffer the more painful consequences – higher unemployment and lower profits.”

They noted that higher interest costs will gradually increase pressure on companies for the foreseeable future, affecting some more than others depending on their creditworthiness and the structure of their borrowings.

“All this means exciting times for corporate bond investors,” they said. “Most obviously, higher interest rates mean ‘income’ is back as a theme. Investors can now lock into meaningful levels of income for the first time in years. Not only that, but when market interest rates fall to reflect lower inflation and a slowing economy, bond prices rise, generating capital gains too. Central banks are likely to start cutting rates in 2024.”

There is considerable uncertainty about the timing and extent to which a slowing or shrinking economy will hit the creditworthiness of borrowers, with variation in effect on individual firms.

“This phase of the credit cycle is one where sector and security selection are very important. Under these conditions, we prefer to focus on high quality companies with strong balance sheets, steady cash flow and resilient fundamentals,” they added.

©Markets Media Europe 2023

©Markets Media Europe 2025