ETFS: HOW THE BUY-SIDE TRADER BENEFITS FROM THE NETWORK EFFECT.

Fixed income exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are increasing in popularity amongst buy-side traders. To realise their true value, traders must ensure they are plugged in to a network of data sources and counterparties in order to price and trade optimally.

Ganesh Iyer, director of global product marketing for Financial Markets Network at IPC and Steve Mickle, director for ETF Trading Solutions at WallachBeth Capital share their market experience of how ETFs can be used most effectively.

How would you characterise the relationship between fixed income ETFs and market liquidity?

Steve Mickle: It’s a positive, long-term relationship. In 2008, fixed income ETFs really got on the map when there were no bids on any of the single bonds, but certain ETFs were trading actively, albeit at discounts, giving access to the bond market. The utility of it is that in a tough environment you can access corporate bond exposure through the ETF easier than the underlying market.

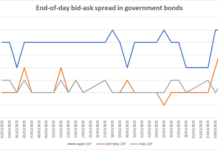

Ganesh Iyer: Today we have all-to-all trading in fixed income but also other types of trading protocols that are quite common. And fixed income ETFs are one solution to fragmentation in the market place due to their liquidity characteristics, diversification benefits and also the ease of trading and price transparency.

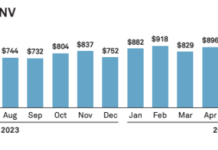

Steve Mickle: As fixed income ETFs have grown by total assets under management as well as total average daily volume in trading, many more options have grown, beyond the flagship products that were around back in ’08. That’s great for institutional exposure and for retail exposure. Bulge bracket banks aren’t able to hold as much risk inventory on single bonds as they used to. That leads to wider spreads when they are selling bonds and less inventory so their prices are less competitive. It’s harder to access things like high yield, or muni exposure for institutions, especially if you are not a massive institution.

How are mechanisms filling in the gaps in the trading fabric left by dealers?

Steve Mickle: Creation/redemption is a crucial element to the well-oiled machine that are ETFs. Behind the scene there is a lot of creation/redemption happening with the big authorised participants (APs). They are adding to the funds, but it’s important to know that there does not have to be a ‘create’ or a ‘redeem’ in a fund for a big purchase or sale to happen. Fund providers say that they are taking in massive amounts of bonds from a big corporate pension or a big insurance company and then relaying the equivalent ETF shares to them, but we don’t see it a lot.

Steve Mickle: Creation/redemption is a crucial element to the well-oiled machine that are ETFs. Behind the scene there is a lot of creation/redemption happening with the big authorised participants (APs). They are adding to the funds, but it’s important to know that there does not have to be a ‘create’ or a ‘redeem’ in a fund for a big purchase or sale to happen. Fund providers say that they are taking in massive amounts of bonds from a big corporate pension or a big insurance company and then relaying the equivalent ETF shares to them, but we don’t see it a lot.

Insurance companies and pensions have to hold single bonds against their liability-driven asset sheet. They have to match up single bonds and their maturities and their durations to events in the future for pension and insurance pay-outs. The possibility of taking single bonds from an institution’s balance sheet and delivering back more liquid shares in an ETF is an exciting one. To mature it will take a long time; an insurance company pushing fixed income money into a managed product is hard, because there is a management fee and they are an insurance company and for 100 years they have been buying single bonds.

From an information perspective, what sort of support do you think buy side desks need when they are going to trade ETFs?

Steve Mickle: The fund providers and Bloomberg are working together to take a better look at actual cash flows of the single bonds, so that on-screen markets can better price ETFs. The cash flow calculations have never been in the system before. That would be useful especially for big institutions that want to know that paying a management fee to buy an ETF instead of buying single bonds will result in tight tracking of the benchmark.

Ganesh Iyer: Today’s fixed income market requires far greater connectivity amongst market participants, more transparency and offers a greater variety of opportunities to trade because there is more buy-side to buy-side trading and more all-to-all trading. There is fragmentation of liquidity venues and a lot of them are using different types of trading protocols.

Steve Mickle: The ETF can be a leading indicator of where the bonds are going to be priced when they finally do sell. Like houses and appraisals; if you had an open market of more houses selling all the time in your neighbourhood you would have a better feel for how much your house is worth.

When you look at the range of counterparties that traders have, how does that network impact the ability that firms have to trade ETFs effectively?

Ganesh Iyer: Having access to an established ecosystem of diverse market participants and connectivity throughout the trade lifecycle, from order creation to order placement, from trade execution to clearing, settlement, recording and market data delivery is really important. The sell side still plays an important role, but there is more pressure on traders because of the capital requirements and constraints that they are facing, so they are just not able to make markets like they used to. That creates a need for a broader network to easily access more counterparties.

Ganesh Iyer: Having access to an established ecosystem of diverse market participants and connectivity throughout the trade lifecycle, from order creation to order placement, from trade execution to clearing, settlement, recording and market data delivery is really important. The sell side still plays an important role, but there is more pressure on traders because of the capital requirements and constraints that they are facing, so they are just not able to make markets like they used to. That creates a need for a broader network to easily access more counterparties.

Steve Mickle: Agreed. We argue that you have to be very intentional when you go out for pricing on fixed income ETFs or you are leaving money on the table. A lot of the biggest pension and insurance companies are just calling one dealer and saying, “500,000 shares of HYG and I am a buyer, where are you?” Better to not tell them what side you are on, not tell them that it’s a big pension fund or a tiny advisor; make them compete for the trade.

Can you give an example of how funds can get added value from the network effect?

Ganesh Iyer: Electronic and voice connectivity to an established ecosystem of counterparties and liquidity venues is crucial for ETFs since they trade simultaneously in a number of liquidity venues and firms often arbitrage price dislocations amongst markets where an ETF is traded. Additionally, if an ETF trades at a discount to net asset value (NAV) of underlying securities, a trader will buy the ETF, exchange it for securities in the ETF’s underlying portfolio and then sell the underlying securities in the market for a profit.

If the ETF is overpriced compared to its NAV, a trader can short-sell it, then buy securities of the ETF’s underlying portfolio, exchange the securities bought for new securities in the ETF and cover the short position with the new securities in the ETF.

All this requires a trading firm to have access to multiple counterparties, broker-dealers, a range of exchanges, prime brokers for leverage and market data / trade lifecycle services for devising strategies and making trading decisions.

Steve Mickle: A small pension client of ours wanted to buy 50k, $5mm of PIMCO 0-5 Year High Yield Corporate Bond (HYS). Electronic screen markets at the time were 99.03 – 99.17 for only 100 x 400 shares. We were prepared to be 15% of ADV. In addition, this is a relatively wide spread for high yield at 14 basis points. We called our best high yield fixed income liquidity providers from our network, and began to aggregate the best two-way markets. We observed multiple bids at 99.01, and multiple offers at 99.20.

However, in our price aggregation exercise we surfaced one liquidity provider who was long HYS shares, and was an aggressive seller at 99.15 (two cents better than the screen offer at the time). The client agreed to jump on this opportunity for price improvement. We purchased the entire block at 99.15, two cents inside the screen offer. This resulted in +2.02 bps of price improvement for our client – based on the ‘Arrival BBO’– from our third-party transaction cost provider, MarkIt.

©TheDESK 2016

©Markets Media Europe 2025