Testimony given to the US House of Representatives on 29 March 2017 suggests the Volcker Rule cannot be directly blamed for poor liquidity in the corporate bond market.

The Volcker Rule, part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, took effect in 2014 and prevents banks from proprietary trading in asset classes including corporate bonds, but not government or municipal bonds, and limits their investment in ‘risky’ trading firms such as hedge funds.

The rule is only one part of the story behind corporate bond illiquidity, said David Blass, general counsel for US buy-side trade body the Investment Company Institute, speaking at a hearing entitled ‘Examining the Impact of the Volcker Rule on the Markets, Businesses, Investors, and Job Creators’ at the Capital Markets, Securities and Investment Subcommittee at the US House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services.

“After the financial crisis and the ensuing regulatory reform, the role of dealers in these markets has changed, with dealers reducing inventory and acting more often in an agency capacity for their customers,” said Blass. “A number of factors may explain why dealers have chosen to reduce their holdings of corporate bonds. These include the Volcker Rule and other regulatory requirements that limit the ability of banks to use their balance sheets to engage in market making activities, as well as increased costs associated with holding corporate debt in inventory.”

Marc Jarsulic, vice president for the Economic Policy Center for American Progress said, “The connection between the decline in bond inventories and the Volcker Rule is in reality not very strong.”

He cited Goldman Sachs research indicating the relative decline in corporate bond inventories from pre-crisis levels reflects the “accumulation of positions in private label mortgage backed securities rather than traditional corporate bonds” and the decline in MBS since.

Charles Whitehead, the Myron C. Taylor Alumni Professor of Business Law at Cornell Law School called for the Volcker Rule to be repealed, noting that, “There are legitimate reasons to be concerned over the risks associated with a bank’s trading operations. But those risks can be more effectively addressed through other means, such as imposing capital charges on a bank’s trading books and the traditional bank regulators’ focus on risk management and assessing a bank’s safety and soundness.”

Broader illiquidity

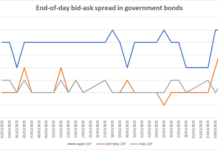

The increased cost of liquidity in the corporate bond market is found in US, European and EM markets, but is not limited to credit trading. Illiquidity has also increased across government bond and foreign exchange markets.

An analyst paper by Bank of America Merrill Lynch noted in October 2016 that “traditional measures such as bid-ask spreads in FX have indeed narrowed in the past few months, our volume-based analysis shows market liquidity has materially worsened… Notably, the frequency and amplitude of outsized volatility events has also increased.”

A similar finding was made for US government securities in 2015 report by the US Department of the Treasury Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission. It was reporting on the flash event of 15 October 2014 in US treasuries which saw yields spike and prices fall over a brief period with no link to underlying fundamentals.

The report noted, “an improvement in average liquidity conditions may come at the cost of rare but severe bouts of volatility that coincide with significant strains in liquidity. The changing nature of liquidity also suggests that the way it is measured may need to be enhanced in order to obtain a more meaningful understanding of the state of the market.”

The corporate bond market is more illiquid than most, due to the number of debt instruments of different tenors issued by each corporate at different times. That vast number often makes exact matching of instruments between buyer and seller impossible.

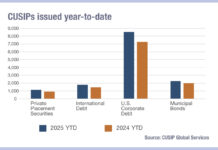

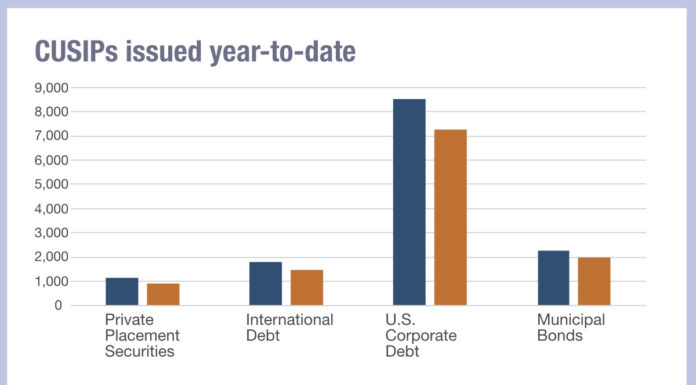

Some testimony at the hearing appeared to miss this point; Thomas Quaadman, executive vice president at the Center for Capital Markets Competitiveness, US Chamber of Commerce, said, “Even though corporate bond issuances have increased, bond market liquidity has decreased with fewer dealers and less market making activity. This has led to unexplained stresses in the marketplace.”

He cited a 2016 CFA Institute report which found that over a five-year period liquidity in high yield investment grade corporate bonds had decreased, with fewer dealers, smaller sized trades and more unfilled orders, while it found no liquidity issues existed for government bonds.

Several speakers referred to a December 2016 Federal Reserve study, which found US bond dealers decreased market making behaviour in periods of stress in high yield US corporate debt.

“Because those dealers make up the preponderance of the marketplace, the Volcker Rule was found to have caused less liquid bond markets during times of stress,” Quaadman said.

Yet Jarsulic noted that this finding by the Fed was not indicative of a wider problem, adding “There is no reason to expect market makers, or any other financial market participants, to act as shock absorbers at times of extreme stress.”

©Markets Media Europe 2025