The macroeconomic fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will continue to constrict liquidity for Europe’s fixed income markets and dictate central bank monetary policy for the foreseeable future, panellists told attendees at the Fixed Income Leaders’ Summit 2022 (FILS) event in Nice.

European markets are particularly vulnerable due to the energy crisis and reliance on Russian oil and gas, while the US Dollar continues to be seen as a safe haven relative to the Pound or Euro.

“Bond yields will continue to rise one year from now,” said Stefan Hofrichter, chief economist, Allianz Global Investors.

“There is underlying inflationary pressure that goes way beyond either the pandemic or Putin. There are also structural supply shocks, linked to deglobalisation and tightness in labour markets.”

Central bankers, from the US Federal Reserve to the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt, have embarked on a huge policy stimulus, in a drastic change of the macroeconomic picture from the low to negative interest rate environment of 2020.

“Central banks will have to do more, and the Fed is committed to do more,” he said. “What has been priced in already by the market is not sufficient. We’re looking at a peak interest rate of 5% plus. Recession is very likely to come in the next 12-18 months, but it will not pre-empt the Fed and other central banks from doing the job.”

He said he thought the dollar was overpriced by as much as 20%, but a correction will not be soon in coming – in part, Hofrichter admitted, simply because the rest of the world is doing worse.

“In the current environment don’t want to bet against dollar, as it’s seen as a safe haven currency,” Hofrichter said. “The Fed is determined to fight inflation, even if they need to do more than so far communicated. Even though we expect a US recession, in the near term there is no need to take an opposite view.”

Europe’s fixed income bond market began to price in the Fed’s hawkish rhetoric this summer, explained Rachel Baxter, head of European bond indexing, Vanguard, with inflation the dominant factor triggering a sell-off in long positions.

Central bankers are unmoved by liquidity pressures, she suggested, but would only intervene for financial stability reasons, such as the Bank of England’s recent £65bn surprise intervention in the government bond market.

“We will see the same from the ECB,” said Baxter. “They are aware of the risks that can come up with a transition to quantitative tightening and rate rises. A true shift in policy will come only if you get inflation sustainably back to target in the long-term.”

Hofrichter agreed that financial stability was the only thing that might knock central bankers off their present course.

“Overheated housing market is one reason to worry. Let’s see if those risks materialise, because the possibility of central banks stepping back is not only about rates,” he said. “We may see pressure coming from fiscal policy, which might prevent central bankers hiking rates as much as they would like to in the first place. Bond yields will continue to price in inflation expectations.”

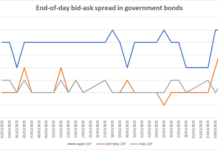

Markets are struggling to price risk amid the volatility, with liquidity risk itself difficult to price, Lee Bartholomew, global head of derivatives product R&D fixed Income, Eurex emphasised.

Recent turmoil in London have meant that the US and Europe are relatively behind the curve, with UK assets underperforming as a consequence, Baxter suggested. “Central bankers are playing catch up. The Bank of England started earlier, but arguably should have done a bit more,” she said.

European investment grade assets are underperforming the US for now, she suggested, looking cheap in comparison, in part because they are more exposed to energy shocks.

Volatility in equities is the underlying factor in pricing credit markets, said Hofrichter. These would continue to rise as a lagged consequence of policy tightening, with credit rises feeding into higher spreads.

On liquidity, Bartholomew and Baxter suggested liquidity frustrations were within acceptable limits and relatively tame compared to previous crises, even as recently as March 2020 during the early stages of the Coronavirus pandemic.

“When you look at what we have been through I’m pleasantly surprised that the market is still functioning well,” she said. “The Gilt situation came closest, but the Bank of England stepped in. Yes you’re paying more to get stuff done, and it’s harder to get stuff done, but we’re still in a functioning market.”

©Markets Media Europe 2022

©Markets Media Europe 2025