By Dan Barnes.

Green bonds issuance is booming and investor appetite growing, making access to markets increasingly important.

The size of the green bond market reached US$200 billion in early 2017, according to analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. In a report issued in March this year, entitled 2017: Enter The Sovereign Green Giants, they found the industry had been elevated by US$92 billion of issuance in 2016 and a further US$19 billion up to 28 February 2017.

Since 1 January 2016, BAML research noted that eight countries and approximately 150 issuers have entered the market using an increasingly diverse set of instruments, including sovereign green bonds and green mortgage-backed securities.

The size of issues is growing. On 30 August 2017, UK energy firm SSE issued a massive eight-year E600 million bond, due to mature September 2025 with a coupon of 0.875 per cent, via the London Stock Exchange (LSE). SSE noted that it was the lowest coupon it had achieved for a senior bond. The LSE reports that transparency and corporate governance are two contributing factors to drive green bond issuers to list their issues, where many bonds are not listed.

Bram Bos, senior portfolio manager at asset manager NNIP, says, “There is clearly a rising demand for investors to do good, and to have more impact products in their asset allocations. Green bonds in their universe are relatively liquid and relatively easy to access for global fund investors. So liquidity is rising sharply in this area, naturally issuers react on that and are moving to issue more and more green bonds.”

Define green

Determining whether bonds are green is a matter for investment managers and investors to agree, when supporting a mandate. The International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) issued its ‘Green Bond Principles’ in 2016 – updated in 2017 – to provide guidance on the instruments based on four components:

- Use of proceeds

- Process for project evaluation and selection

- Management of proceeds

- Reporting

These are typically used by asset managers within their own process to assess the viability of instruments for inclusion. Bos says the firm takes an in-house approach to analysis, to determine what is green and what is not.

“We have three steps; we look at the Green Bond Principles, we look at the Climate Bond Initiative taxonomy, the UK NGO that defines what is green and what’s not,” he says. “Then thirdly we also look at the profile of the issuer to avoid the ‘green washing’. But it’s all done in-house here.”

Accessing the market

As a subset of the fixed income market, green bonds could potentially be far less liquid and more expensive to access than the broader universe of instruments. There are too limited a number of bonds for most firms to build an index, however there are ways for investors to access green bonds within a wider portfolio.

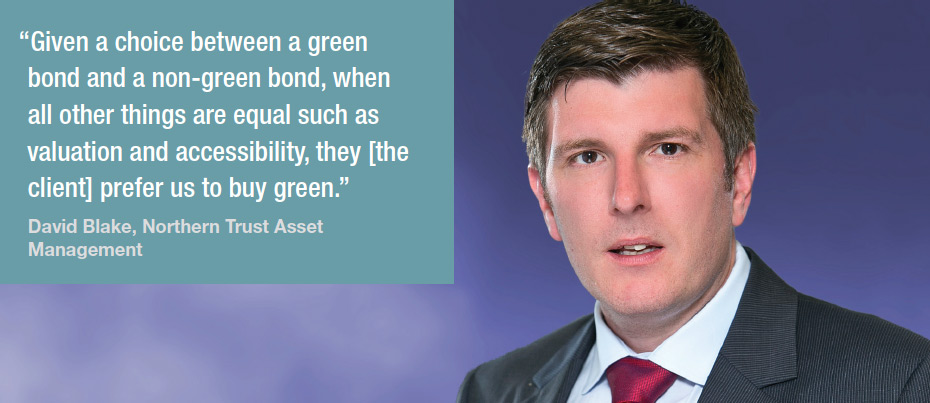

“Within our indexing business we have clients who assert a soft preference for green bonds in their portfolio,” says David Blake, director for International Fixed Income at Northern Trust Asset Management. “Given a choice between a green bond and a non-green bond, when all other things are equal such as valuation and accessibility, they prefer us to buy green. What we won’t to do is buy a green bond if it doesn’t fit the portfolio construction or the price is too high.”

Applying discretion to the investment process requires that the connection between portfolio management and trading desk is supported in order to ensure a two-way flow of information.

Jorryt Peperkamp, senior trader at NNIP says, “We always have an open dialogue ongoing throughout the whole trading process. So, from the moment the order has been raised in our order management system that basically opens up the dialogue between the portfolio manager and the trader as well. So, basically it then gets from the start of the order to execution of the trade.”

The primary market remains the single best way to access the corporate bonds market, whether green or not, and observationally portfolio managers and traders report hardly any difference in terms of pricing green vs non-green.

“There may be a basis point or two in yield, as premium for the green bond over a non-green bond from the same issuer or at the same maturity level,” says Blake. “You rarely get a direct comparison; there is a premium in the primary markets, and we see the same sort of new issue premium versus existing bonds, green or otherwise, for a particular green bond, or a particular issuer. You do tend to see a little bit of performance at the break but it’s marginal.”

Bos concurs, noting that the process and allocation is largely the same, the only difference being that sometimes issuers differentiate between green bond firms and green investor’s versus non-green investors.

“So the allocation for green bond funds can be a little bit higher, [against] the ones who do not have a green bond fund, or are not seen as a green investor,” he says.

Given the increasing scale of green bond issuance – evidenced from the SSE deal and anecdotally from asset managers – long-only firms expect liquidity to increase in the market allowing them to prosper. However, Ulf Erlandsson, head of fixed income at alternative asset manager Strukturinvest, argues that some long-only managers will have issues sourcing enough green bonds, and also will have issues with having portfolios with very long duration at very low yields, meaning they are not able to offer attractive yields today and are at risk in any upwards interest rate scenario.

“In contrast, alternative asset managers can use techniques to generate better yields today, and hedge out duration risk in a rates rising scenario,” he says. “Given the challenges in the market environment we need to take more and smarter risks, given global warming we need to have more impact.”

One step beyond

Moving beyond the acquisition of issued bonds on the primary market, there can be other options for generating yield whilst trying to control costs. In secondary trading, firms do report a more distinct premium, largely because investors operate a buy and hold policy.

“In secondary markets, if you want to go and get it you are probably going to have to pay a little bit more, but again not much,” says Blake. “That’s a lot to do with the investor. You do have dedicated investors with dedicated preferences, they will tend to hold on to them. So that makes sense in terms of supply and demand dynamics.”

Erlandsson, adds that selling bonds is far less of a problem as a result. “In markets like today, liquidity is mainly an issue for the buying of bonds because of the buy and hold tendencies,” he says. “Where bonds outperform in the weeks following primary market issuance, if you sell them and then reinvest in newly issued green bonds you can support the market further.”

Erlandsson, adds that selling bonds is far less of a problem as a result. “In markets like today, liquidity is mainly an issue for the buying of bonds because of the buy and hold tendencies,” he says. “Where bonds outperform in the weeks following primary market issuance, if you sell them and then reinvest in newly issued green bonds you can support the market further.”

The market for designated green derivatives is limited notes Peperkamp, “I have not seen any bond futures, or credit default swaps specifically on green bonds. Having said that, the single name CDS market has declined very, very sharply over the past few years. I have seen signals in the street that it is picking up, but I have not seen it personally.”

Where investment managers have flexibility on their mandate and can access derivatives, it is possible to use different instruments or trading approaches to increase returns within the parameters of green trading.

“One option is to buy the green bond from the issuer, then sell credit default swap protection on top of that,” says Erlandsson. “That lowers the costs of financing not only on green bonds but the whole debt capital structure, so it entices firms to issue green bonds and adds yield to your portfolio.”

They can also look at long-short strategies which specifically target green instruments for going long, whilst picking bonds to short that have a negative impact on the environment.

“You do need to have experienced fixed income traders to make these strategies work, across the cash bond market and derivatives markets,” Erlandsson observes.

©Markets Media Europe 2025