NETS CAST WIDE AS HIGH YIELD IS SPREAD THIN.

With Third Avenue and Lucidus putting high yield in the headlines, traders and portfolio managers are defining liquidity relationships more acutely to support their needs. Lynn Strongin Dodds reports.

Research from Barclays indicates high-yield US debt – bonds rated double B plus or lower by one of the major rating agencies – slid more than 5%

in the first six weeks of 2016 with total returns over the past 12 months falling below minus 10%. By contrast, their European counterparts slipped just 4.7% during the same timeframe. For investment managers and buy-side traders, strong oversight of portfolios and trading relationships is needed to limit losses and handle any worsening of liquidity.

Nick Cox, global head of fixed income trading at J.P. Morgan Asset Management, says, “We do not feel that broader market liquidity has deteriorated significantly. If you normalise for short-term volatility we are still able to execute what we need to trade by going to more intermediaries and pools of liquidity.”

Concern about high yield funds and market liquidity was brought into focus when Lucidus Capital Partners, a US$900m high-yield credit fund and mutual fund, Third Avenue Management both went into liquidation last December, with higher than average weightings into risky energy related investments, but with the latter’s collapse marking the biggest mutual fund failure since the global financial crisis.

“Obviously, high yield has had a bad start, but December was also torrid because of the energy and commodity sectors struggling with the end of the commodity boom to emerging markets” says Jonathan Butler, head of European Leveraged Finance at buy-side firm PGIM, “These energy related sectors account for around 10% of the US high yield indices, and predictions from rating agencies and strategists are that the default rates could be between 4% and 6%. This estimate is only 1% to 2% in Europe which has a higher quality index, more BBs and less triple Cs as well as less exposure to energy and minerals.”

As one industry participant put it, “If you look at Third Avenue and Lucidus, the problems had less to do with liquidity than a risky bet. They aggressively bought distressed assets in the energy field before the fourth quarter and the hope was that the market would move in their favour. However, as things detonated, it was clear that the tide was going against them.”

Over 90% of Third Avenue’s US$788.5m Focused Credit Fund was in issues rated CCC and lower. Redemptions spiked as energy prices plunged and instead of selling bonds at fire sale prices to meet investors’ demands, the firm firmly shut its doors. While it is unclear how long it will take the fund to settle its affairs and make final payments to shareholders, losses incurred of 40% since the middle of 2014, means many shareholders are facing net losses.

Figures from Interactive Data show that from February 2015 to November 2015, the portfolio liquidity score of the iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond ETF held its own during the period, dipping from approximately 9 to 8.7. By contrast, the Third Avenue Focused Credit (TFCIX) initially had a lower liquidity score at around 6.9, reflecting lower relative liquidity versus the comparable HY index, and subsequently declined further to approximately 5.8 during the same period.

Authorities have indicated concern about liquidity in this space. The liquidations triggered a probe by US regulator the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Examiners at the regulator reportedly sent detailed requests to mutual and exchange-traded funds seeking information about how they price less liquid securities, and whether certain parties have ever challenged those prices. The move was also part of the US watchdog’s proposed new rules issued last September that would require funds to maintain a minimum cushion of cash or cash-like investments that can be sold within three days.

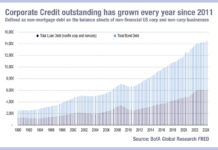

The SEC’s investigations are geared more towards the retail investor who has become a larger constituent of the US market. However, even the more sophisticated investors have been hit by the increased volatility, smaller trade lot sizes and shrunken inventory due to banks sitting on the sidelines. The toll of tighter Basel III leverage and capital ratios on banks’ balance sheets and their willingness to hold risky assets has been well documented. Things came to a head late last year though when Goldman Sachs sounded the alarm that the inventory of corporate bonds held by the Federal Reserve’s 22 primary dealers fell below zero for the first time. Meanwhile, the Bank of England estimates there has been a 75% reduction in the overall bond inventories of dealers in the US$10 trillion global corporate bond market since 2008. High yield in the US is around US$1.8 trillion, according to J.P. Morgan research.

Casting the net wider

Institutional investors have taken different measures to offset the lack of depth by trading with a broader set of banks and non-bank participants as well as tapping into platforms. “We are definitely seeing people looking for alternative ways to route their orders versus the traditional broker dealer-centric model,” says Bill Gartland, senior director of evaluations at Interactive Data. “This is why I think MarketAxess’ Open Trading, [which does not require dealers to be on one side of the trade] is gaining more traction.”

Institutional investors have taken different measures to offset the lack of depth by trading with a broader set of banks and non-bank participants as well as tapping into platforms. “We are definitely seeing people looking for alternative ways to route their orders versus the traditional broker dealer-centric model,” says Bill Gartland, senior director of evaluations at Interactive Data. “This is why I think MarketAxess’ Open Trading, [which does not require dealers to be on one side of the trade] is gaining more traction.”

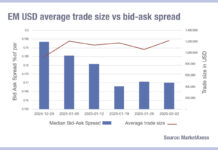

According to MarketAxess, the number of firms participating rose to 469 in the fourth quarter, from 307 in the same period last year, while over 13% of combined US high-grade and US high-yield volume on MarketAxess now takes place via Open Trading protocols, up from approximately 7% a year ago. The firm reports that Open Trading average daily volume rose 100% to US$446 million, during the time frame while a total of over 57,000 transactions was completed in the last three months of last year compared to 28,000 in the same period the previous year. In addition, firms also clocked cost savings of 51 cents in US high yield compared to the best-to-dealer cover price in December 2015.

“Asset managers can still get good coverage but if you are a global asset manager sourcing liquidity has become more expensive and volatile,” says Gareth Coltman, European product manager at fixed income trading hub MarketAxess. “The smaller firms are struggling to get liquidity at a lower cost. The traditional way was to approach a small number of players, but Open Trading has taken off the restrictions and enables firms to access a wider range of both buy- and sell-side participants including those who may have a specific speciality in a sector or region.”

J.P. Morgan’s Cox says, “A few years ago, the top ten to fifteen counterparties would have been able to provide liquidity across broad ranges of securities and asset classes at efficient cost levels. However, outside a very small number of true ‘full service’ providers, we see most dealers focussing on a limited range of asset classes or sectors. Therefore we are dealing with a broader range of specialist or niche liquidity participants to fill the gaps, as these specialists have the natural inventory or axes that result in more attractive pricing.”

Asset managers are also targeting specific names in terms of investments. “You have to be discriminating,” says Philippe Berthelot, managing director, credit, Natixis Asset Management. “We are overweight Europe because the market has grown from being one tenth the size of the US to one third and is still developing. However, you need to analyse balance sheets and have good timing before buying, but you can grab 5.5% yield which is not that common today.”

In the US, Butler sees value in consumer oriented bonds which should not be impacted by the strengthening dollar and benefit from a resilient consumer economy. “We believe that GDP is positive and that these securities can benefit from low energy prices and low interest rates. We also like this sector in the UK for now. In Europe QE (Quantitative Easing) is assisting the high yield sector more broadly, assisting industrials, exporters and the broad economy – from a low base. In general though we pick individual credits and try to avoid those that will blow out. The focus is less on the liquidity than having strong credit research teams who can do the analysis.”

©TheDESK 2016