Still fighting for the depth of US and Japanese bond markets, China’s liberalisation of derivatives trading bodes well for market liquidity. Lynn Strongin Dodds reports.

After almost 30 years, Chinese authorities have unlocked the door of its domestic bond futures markets for the banking sector. The country’s five largest banks are the first to be invited to participate. While there is no timeline, their foreign counterparts are likely to follow as part of the government’s ongoing programme to broaden participation in its US$13 trillion bond market, the world’s third largest.

Despite the size, the market still does not have the depth of its US or Japan counterparts which rank number one and two, respectively on the bond charts. According to figures from Dealogic, although all countries suffered as the pandemic unravelled in the first quarter, debt capital volume in China was US$209.2 billion compared to the US$1.01 trillion in the US in the first three months.

“The size of the Chinese bond market is still low relative to its GDP and there is room for it to grow,” says JC Sambor, head of emerging markets fixed income at BNP Paribas Asset Management. “If you look at the foreign share of Chinese government bond ownership it has increased to 8% from 4% but that is quite low compared to the 50% to 60% in developed markets and the 35% to 40% in Indonesia and 30% to 35% in Malaysia in emerging markets.”

Brad Gibson, senior vice president and co-head of Asia Pacific fixed income at AllianceBernstein says, “Having a widely used and liquid futures market is an important step in the Chinese government’s wider strategy to develop a deep and liquid bond market.”

It came as no surprise that the futures market first opened to the five largest state-owned banks – Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Agricultural Bank of China, China Construction Bank and Bank of Communications – to deepen the well of liquidity. Overall, analysts estimate that when the bond futures market is fully opened to banks and insurers, it could bring in around Rmb30 billion ($4.2 billion) of additional funds, expanding the market by 20%.

“Going to the five biggest banks makes sense because they dominate liquidity,” says Gibson. “We believe foreign investors will also ultimately be allowed to use China bond futures but the short-term focus for China is to attract physical inflows into its markets so foreigners will need to wait. Foreign investors are also unlikely to pull the trigger on using futures until they see how the market and liquidity develops.”

Cassandra Cheng, head of FICC China at SGX agrees, noting that allowing Chinese commercial banks, which hold around 67% of the outstanding Chinese government bonds (CGBs), into the CGB futures market will help to improve liquidity in both the cash bond and futures markets. “I think opening up to offshore institutions is certainly on the agenda and Fang Xinghai, vice chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), has mentioned this on many occasions too,” she says. “We believe the question is not whether or not, but rather when and how.”

Cheng points to an article Xinghai wrote in last year’s International Monetary Fund paper ‘The Future of China’s Bond Market’, where he stated that allowing domestic banks to participate in the Treasury futures market was a first step in contributing to better interest rate risk management which in turn would increase overall cash market liquidity.

Cheng points to an article Xinghai wrote in last year’s International Monetary Fund paper ‘The Future of China’s Bond Market’, where he stated that allowing domestic banks to participate in the Treasury futures market was a first step in contributing to better interest rate risk management which in turn would increase overall cash market liquidity.

“The same is true of foreign investors, who increasingly have access to the domestic bond market through the different quota schemes and China’s Interbank Bond Market through Bond Connect but have not been able to participate in the Treasury futures market,” he added.

Bond Connect was one of the most notable developments in the government’s ongoing programme to reform capital markets. Introduced in 2017, it allows international investors to trade in Chinas onshore bond market via Hong Kong. More recently, last year, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) eliminated the strict quota restrictions placed on its qualified foreign institutional investor schemes.

Back to the future

This is not the first time that Chinese banks are participants in the futures markets. They were allowed to buy and sell contracts for future delivery of a bond in 1992 when the market was launched on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. Three years later, regulators were forced to close it down when Shanghai Wanguo Securities, the country’s largest brokerage at the time, collapsed triggering a panicked sell-off.

While the market was unlocked again seven years ago, it was limited to brokerages and fund management groups. Banks as well as insurers were excluded and continued to rely on selling bonds or using interest rate swaps to hedge. The challenge is that these instruments are not as liquid and transparent as futures which provide a much more efficient means for banks to hedge their risks on their balance sheet.

Initially though, “banks are likely turn to the loan prime rate (LPR) based IRS for liability hedging, and CGB Futures for bond portfolio hedging,” says Cheng. “For fund managers, they could use IRS to adjust bond portfolio duration, but there will be a basis risk. It is possible that part of the IRS turnover / trading interests will be shared by CGB futures. It is still too early to quantify the impact.”

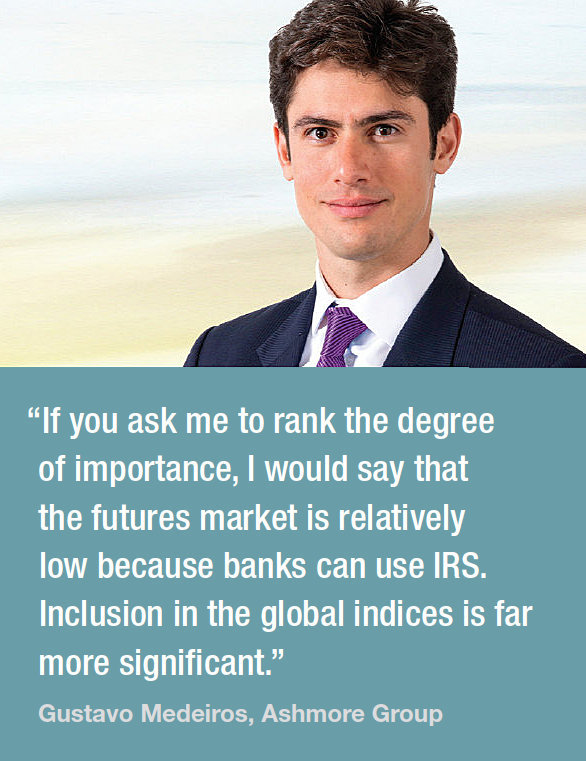

Gustavo Medeiros, deputy head of research at Ashmore Group, also believes foreign banks would use IRS and would want to see more liquidity before they would use futures. However, he places far more significance on the developments in the benchmark world.

Gustavo Medeiros, deputy head of research at Ashmore Group, also believes foreign banks would use IRS and would want to see more liquidity before they would use futures. However, he places far more significance on the developments in the benchmark world.

“If you ask me to rank the degree of importance, I would say that the futures market is relatively low because banks can use IRS,” he adds. “Inclusion in the global indices is far more significant. It allows for much greater issuance and greater liquidity over the long term.”

Last April, yuan-denominated government bonds and policy bank securities started to be phased into the US$54 trillion Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index over a 20-month period while JP Morgan Chase began adding Chinese government debt to its indices at the end of February 2020. Since the Bloomberg Barclays inclusion, analysts estimate that around US$69 billion in foreign money has piled into Chinese domestic bond markets, with roughly a third of these inflows emanating since the end of September.

Hayden Briscoe, head of fixed income for Asia-Pacific at UBS Asset Management also believes market participants should not underestimate the magnitude of the inclusion of Chinese bonds.

“It is the single largest change in capital markets in anybody’s lifetime as central banks, sovereign wealth funds and index trackers move to reach index weight,” he says. “We estimate that there could be $3 trillion in inflows. The market is particularly attractive today as it is the only one generating real yields relative to other countries.”

During the first quarter, as the pandemic swept through the world and lockdowns ensued, monetary policymakers pushed interest rates to historic lows, including negative rates in Japan and parts of Europe. The result was that bond yields dropped dramatically. Yield on the 10-year US Treasury, for example, slid by 95 basis points to 0.64% from mid-February to April 20. By contrast, its Chinese counterpart, albeit hit, had a much higher yield than Treasuries or similar government debt – 2.55%. This represents the biggest gap between the US and Chinese government debt in nearly nine years.

©The DESK 2020

©Markets Media Europe 2025