By Josh Weinberger & Dan Barnes.

The famously holistic service has broken out the Instant Bloomberg chat function for non-terminal users, delivering what looks like victory for stalking horse Symphony. However banks may want more.

Banks can break a company if they do not like its pricing. Bloomberg appears to have found this out. In an unprecedented move, the data and communication giant split out its messaging service to be accessible from a terminal for non-terminal users within a firm, with a US$10 a month charge to each additional user.

The separate service, Enterprise Instant Bloomberg (IB), is in production for a select group of customers, who started using it at various times from December 2016 to the present.

“We’re adding immediate value to existing Terminal users’ workflow, allowing them to communicate with employees who aren’t traditional Terminal users,” says a Bloomberg spokesperson. “…thanks to Enterprise IB, everyone in a Terminal user’s firm who needs to communicate with Bloomberg Terminal users in a compliant manner on a single platform can do so.”

The new feature, which can be used for internal and external communications, offers a lower cost alternative to rival bank-backed messaging platform, Symphony, which was launched by a consortium of banks in 2015, based on a $20-per-user monthly charge. However, it may not be pricing but control that banks are after with Symphony.

The pressure to develop an alternative to Bloomberg began in earnest when investigators into LIBOR-rigging discovered enormous amounts of material relating to sell-side price rigging across LIBOR and other instruments within Bloomberg chat logs.

While the data provider is clear that ‘All chats are archived and auditable, enabling you to fulfill compliance requirements’ it appears banks had not considered the accessibility of third-party chat to regulators, particularly inter-company chat over which they had no control. If a company’s communications are accessible without that company’s consent, or potentially knowledge, that creates risk.

While the data provider is clear that ‘All chats are archived and auditable, enabling you to fulfill compliance requirements’ it appears banks had not considered the accessibility of third-party chat to regulators, particularly inter-company chat over which they had no control. If a company’s communications are accessible without that company’s consent, or potentially knowledge, that creates risk.

The evidence gathered from Bloomberg messaging logs supported cases that cost banks billions of dollars in fines. Banks subsequently began to ban their traders from Bloomberg chat rooms and they began to talk with each and rivals about building an alternative.

Leverage

When banks want to push down prices at a service provider, their proven modus operandi is to create competition. They first form a consortium, which builds a rival platform with lower pricing, and then use that as leverage. They use, or threaten to use, that platform until the incumbent drives down its own fees.

For example, when banks complained about the London Stock Exchange’s (LSE) pricing in 2006, they formed ‘Project Turquoise’ as a rival, and registered it as a multilateral trading facility (MTF) under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) which came into effect in 2007.

“MiFID wasn’t a necessary condition for something like Turquoise to happen but it was helpful.” said Adrian Farnham in 2008, as Turquoise’ chief operations officer. He cited dissatisfaction with the incumbents and new technology as major triggers for the Turquoise launch.

At the time banks denied Turquoise was a ‘stalking horse’ and argued it was a viable business. It made a loss of £15.7 million in 2008, which was blamed on market volatility, which prevented banks from fulfilling their liquidity provision agreements. They did not renew their agreements in 2009.

That year the LSE revised its own fee model and replaced its expensive technology with a new lightweight version, MillenniumIT. In its February 2010 pre-close update, the LSE hailed a reduction of 0.06 basis points in the amount users were paying to trade.

Then in February 2010, having addressed the two concerns which Farnham said had led to the launch of Turquoise, the LSE completed a deal to acquire the majority share in Turquoise, helping the banks who were burdened with a loss-making platform and re-establishing the positive relationship between banks and the exchange. If Turquoise had been intended to drive down trading costs, it had succeeded.

The commercial pressures

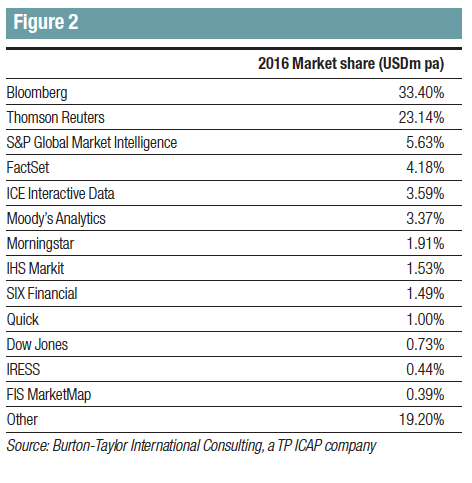

Similarly, if banks wanted to drive down the cost of Bloomberg chat, they also appear to have succeeded. The cost of Bloomberg is a perennial concern. It has 325,000 terminals in use, as estimated by specialist Burton-Taylor International Consulting. Faced with the average annual bill of US$22,600 for each terminal – according to the consultancy’s figures – traders are concerned that costs have not declined as they faced budgetary pressures.

Bloomberg is enormously successful. In fixed income, which is built upon over-the-counter (OTC) dealer-to-client transactions, it is a dominant force. In The DESK’s annual ‘Trading Intentions’ research, buy-side traders have consistently rated Bloomberg as the most highly rated tool for finding liquidity for the last three years. In 2017, 74% of buy-side traders classified themselves as ‘Major users’ of Bloomberg as a platform for aggregating liquidity – up from 56% the year before – and 24% classified themselves as ‘Users’, implying a 100% user footprint on asset managers’ trading desks. Bloomberg was jointly ranked as the ‘most preferred’ tool for finding liquidity alongside MarketAxess in 2017.

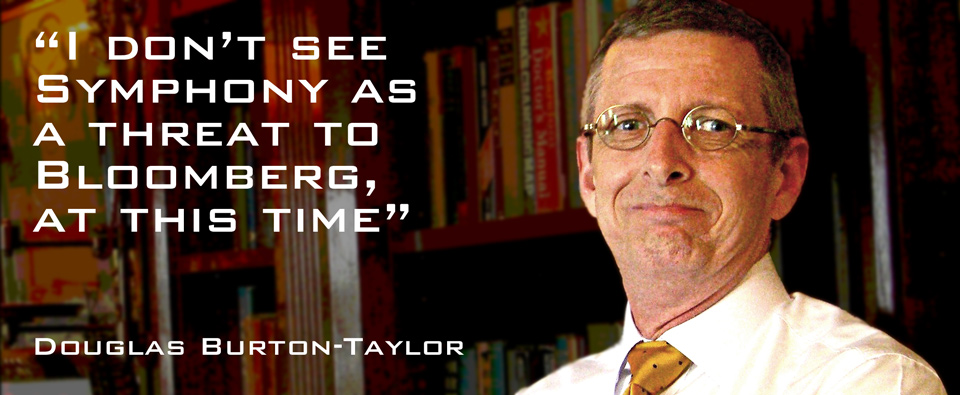

“[For the buy side it offers] complete integration of workflow from idea, to research, to analysis, to execution,” says Douglas Taylor, managing director at Burton-Taylor International Consulting.

Traders in an OTC market say that having an accepted norm can be a real advantage – even if the norm is not used for internal measurements – because the lack of a centralised marketplace makes most technology non-standard.

“Bloomberg Analytics is helpful in that it’s an industry standard,” says one buy-side head of fixed income trading. “If I price a swap on Bloomberg I know that the sales person at the other side is pricing it on the same calculator. But if you work in a large asset manager it’s probably a less compelling proposition as large managers have in-house analytics.”

Bloomberg’s problems began with the LIBOR investigations. Then it was discovered in 2013 that Bloomberg journalists could access log-in data on users, access which Bloomberg restricted in May 2013. That same month over 10,000 historical messages from traders were made public online, which Bloomberg said had been forwarded with client permission to be used for internal testing and then released by accident. An outage that delayed a UK government debt sale in April 2015, plus a failure of the Bloomberg chat system in November 2016, compounded worries that users had too many eggs in one basket.

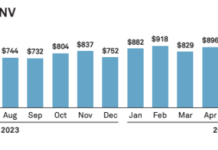

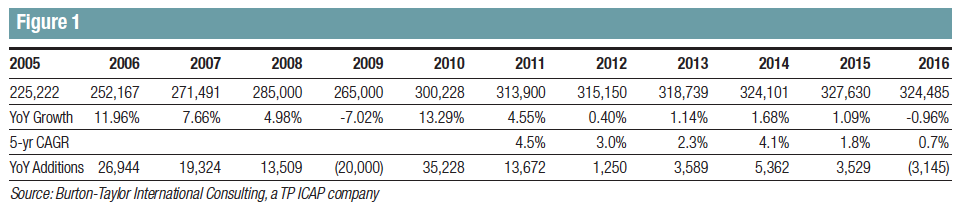

Burton-Taylor International Consulting estimates there was decline in use of 3125 terminals, translating to US$70.6 million in revenues, between 2015-16 (see Figure 1), the first annual fall since a decline in licensing of 20,000 terminals in 2009, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers. On the buy side this fall is attributed to staff who used Bloomberg primarily for services like messaging, rather than revenue generation, having it removed.

Project Symphony

Symphony is a US$20-a-month communication and content platform that incorporates elements and individual tools contributed by a ‘Who’s-who’ of Bloomberg’s rivals. It was launched in 2015, led by Goldman Sachs and originally based on the bank’s technology. It now incorporates news from Dow Jones, messaging technology from Markit, and has a collaboration with Thomson Reuters to support the exchange of data between users of both systems, the latter announced in 2017. Its cloud computing business is available on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). It claims to have 200 firms and 235,000 users connected, with some 20,000 understood to be at JP Morgan.

For the buy-side trader Symphony provides community. Reuters’ 2017 partnership with Symphony provides some degree of data. On 4 October 2017, Symphony announced it would launch Symphony Idea Engine, to connect buy- and sell-side counterparts using intelligent machine-based filtering via ‘Symphony Signals’. It is designed to match relevant information requests from the buy side with appropriate sell-side counterparts to support transactions. This could potentially be used to communicate trading requests.

The global head of fixed income trading at a large asset manager says, “Initiatives such as Symphony challenge the community aspect of Bloomberg, but everybody has got email already so there are relatively low barriers to challenging that. It is the huge store of reference data which is going to be very hard for anybody to encroach upon.”

Bloomberg reports offering the new deal to distribute Bloomberg messaging access to non-terminal subscribers at US$10 a month, half the price of Symphony in early 2017. Several questions are open and will determine future use of both platforms.

The first is whether US$10 a month is a big enough price difference to entice banks from Symphony to Bloomberg. Based on Symphony’s own user figures – averaging 1175 users per firm – the users would save on average US$11,750 a month, the equivalent of paying for one Bloomberg terminal for six months.

The second is whether Symphony is competing on price or on control of messages. If banks need control, they are not going to be swayed by US$10 a month.

The third question is whether the buy side will buy in to one messaging platform over another. It would seem that Bloomberg’s lower cost offering might prevent buy-side firms moving to Symphony as they are heavy Bloomberg users, but are most challenged by its cost.

Taylor says, “Bloomberg will not reduce terminal pricing or segment the terminal in any way that could significantly impact terminal revenue. Should users wish to expand Bloomberg services beyond the terminal, to their other offerings, there can be negotiated deals for those non-terminal services.”

©TheDESK 2017

©Markets Media Europe 2025