The European Commission (EC) has opened an in-depth investigation into the proposed acquisition of Refinitiv by the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) under the EU Merger Regulation.

At present LSEG’s market cap is about US$35.5 billion and Deutsche Börse’s about US$32 billion. By comparison in the US, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has a market capitalisation of US$60 billion, Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) has US$49.6 billion, and Nasdaq US$18.9 billion. US authorities have allowed CME and ICE to grow to this size by acquisition. By contrast several expansion efforts by LSEG and DB, including a merger, have been quashed.

This deal will be a barometer for further growth appetite in Europe. It should not be affected by the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU), as the EC has the power to rule over mergers and acquisitions that impact its markets.

“Jurisdiction is triggered by effects in the European Union (EU), not location of the legal entities and established at the time of announcement/signing,” explains Matthew Readings, partner and global antitrust practice group leader at law firm Shearman and Sterling. “The only question around Brexit is whether UK gets parallel jurisdiction, but it should be done and dusted before that becomes a possibility.”

Switzerland’s non-EU status did not prevent its domestic market operator SIX Group recently acquiring EU-member Spain’s exchange and infrastructure operator, BME.

The LSEG/Refinitiv deal has been challenged on the strength that the combined entity would have in Europe. The EC has to decide if that strength would contravene competition rules. Some market observers believe that for European exchanges, it will be impossible to reach the size of US rivals.

“You won’t be allowed to [build that scale] in Europe, because you are not allowed to decommission any legacy exchanges and all of the national regulators still exist,” says Ken Monahan, senior analyst at Greenwich Associates.

EC’s concerns laid out: Bond trading

As a single entity, LSEG/Refinitiv will combine ownership of MTS and a controlling stake in Tradeweb increasing its bond trading power, particularly in European government bonds which the EC highlighted; it will manage derivatives and clearing through controlling stakes in Tradeweb and clearing house LCH; and it will own a large combined indexing business.

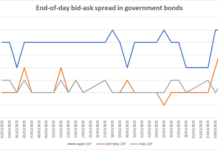

To give an idea of the size of its combined bond trading operations, in 2019, Tradeweb’s European government bond average daily volume (ADV) was US$22.2 billion (€19.4 billion). Although MTS does not disclose monthly figures, based on its total trading volume in 2019 it had an ADV of €14 billion across all of its cash bond trading in Europe and the US.

The ADV for government bond trading in the whole of Europe in 2019, as captured by MarketAxess data, was €71 billion in 2019. MarketAxess captures at most around 80% of European volume, which would suggest the real ADV is €88.7 billion, a figure that several experts estimated was still probably below the real total. Getting a more accurate picture is harder as there is no centralised tape of bond trade prices, and many big players, such as Bloomberg, do not report their European government bond trading volumes.

Therefore, the two platforms with combined maximum ADV of €33.4 billion would have traded a maximum 33.4% share of European government bond trading in 2019.

The EC’s initial market investigation said they are “close competitors in this space, in particular regarding trading between dealers and investors.” The market investigation also suggested that “it is difficult for a new trading venue to attract clients in sufficient numbers and become a real alternative to incumbent venues.”

EC’s concerns laid out: Derivatives trading and clearing

Derivatives and post-trade integration would not expand LSEG’s clearing business, but the proposed transaction would lead to a “combined entity with significant market power [in] trading and [in] clearing.”

The EC says that, “The attractiveness of both trading venues and clearing houses in over the counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRDs) increase with the number of clients using their services” and that “the barriers to entry are high and customers rarely switch trading venues or clearing houses.”

Switching between central counterparties (CCPs) for OTC clearing to increase competition is actively discouraged by Recital 73 of the EC’s European Markets and Infrastructure Regulation. It says that the scope of interoperability arrangements should be restricted to transferable securities and money market instruments “given the additional complexities involved in an interoperability arrangement between CCPs clearing OTC derivative contracts.”

Interoperability for listed derivatives between clearing houses such as Eurex, ICE and LCH was mandated for July 2020 by the revised Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II). However, on 23 June 2020 that was delayed by the Presidency of the European Council and the European Parliament until 4 July 2021, as a result of the COVID 19 crisis.

Whether a single entity owning a clearing house and a venue would change the barriers for new entrants, or affect levels of switching for customers would need to be determined by the investigation.

The Commission’s point that it is difficult to launch new trading venues in either the derivatives space or the fixed income space is correct, but unless there is a plan underway to resolve that point, deals will be delayed in perpetuity.

The Commission’s final two concerns, which suggest that ownership of data supply and indexing businesses could lead to a withdrawal of data for other aggregators and index providers have proven less of a concern for investment analysts looking at the deal.

Kyle Voigt and Matthew Moon from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods noted on 22 June that the worries expressed by European authorities were predictable.

“We believe that MTS will likely be divested,” they wrote in an analysts’ note. “With respect to the second area of concern listed above, if the European Commission requires a remedy to this vertical integration issue, this would be more problematic for [LSEG], as this would likely force a divestiture of [Tradeweb]. We view [Tradeweb] as a key strategic asset, and the crown jewel of this transaction.”

Where are the borders to growth?

The European Commission has permitted many mergers between market operators. Switzerland’s SIX Group acquired Spain’s BME on 11 June 2020 for €2.57 billion and Euronext acquired Oslo Bourse in 2019 for over €620 million, while historically LSEG was permitted to acquire Borsa Italiana in 2007 along with its bond trading business, MTS.

Equally US firms have been able to acquire European market operators. The 2007 merger between NYSE and Euronext was a precursor to that group’s subsequent acquisition by the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) in 2013, which gave ICE control of Europe’s second largest derivatives market, LIFFE. It subsequently divested itself of the less profitable Euronext. The CME Group’s purchase of the UK’s Nex Group in 2018 gave it the lion’s share of interdealer US government bond trading, on top of its existing dominance in US Treasury derivatives market.

However, larger European exchange mergers have been prevented. A Deutsche Börse and NYSE Euronext deal was blocked by the Commission in 2012. LSEG and Deutsche Börse have attempted merger and acquisition (M&A) activity on several occasions, the most recent attempt in 2017 failing, due to an EC anti-trust ruling.

Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, in charge of competition policy, said at the time, “The merger between Deutsche Börse and the London Stock Exchange would have significantly reduced competition by creating a de facto monopoly in the crucial area of clearing of fixed income instruments. As the parties failed to offer the remedies required to address our competition concerns, the Commission has decided to prohibit the merger.”

The question Europe will need to face with this deal is; will the EC allow European champions to develop that are the equal size to those in the US and China?

A comparison with the US model

While European authorities have repeatedly prevented large scale mergers of European trading infrastructure, the US has not. That has led to dominant market operators, notably in fixed income across cash and derivatives.

On the trading front, in 2019 CME Group had an average monthly market share of 46.4% in cash US Treasury trading thanks to its acquisition of Nex Group, according to data from Greenwich Associates. CME Group also owns US Treasury future trading through acquisition.

By comparison, Tradeweb had an average of 22.8% market share for cash trading, and Bloomberg 15.5% market share. In the dealer-to-client trading segment only, Tradeweb has a much larger share of the market, with Bloomberg a close second.

The US has also supported scale in post-trade. It has a de-facto post-trade utility, the Depositary Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC), which evolved through a stream of mergers between rivals and is owned by market participants.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has proven Europe wants greater scale in post-trade by creating its own pan-European settlement system, Target 2 for Securities (T2S), to increase post-trade efficiency.

Fifteen barriers to the efficient functioning and development of cross-border capital markets in Europe were identified in a report in 2001 published by the Giovannini Group. T2S was established to overcome these, but took 16 years to go live and Monahan believes there are other barriers to efficiency, such as national infrastructure and regulators, which also potentially prevent progress.

“Addressing and resolving the list of Giovanini barriers [to cross-border clearing and settlement of securities in the EU] is necessary but not sufficient,” he says.

The EC as an institution has been open to deals between EU and non-EU firms, and it has set out clear reasons for its decisions against deals when they have been made.

What it must consider, whether in this deal or Deutsche Börse’s next foray, or indeed if SIX Group or Euronext expand further, is whether it will allow Europe’s champions to be capital market operators that can rival their peers, or whether to restrict them.

©Markets Media Europe 2025